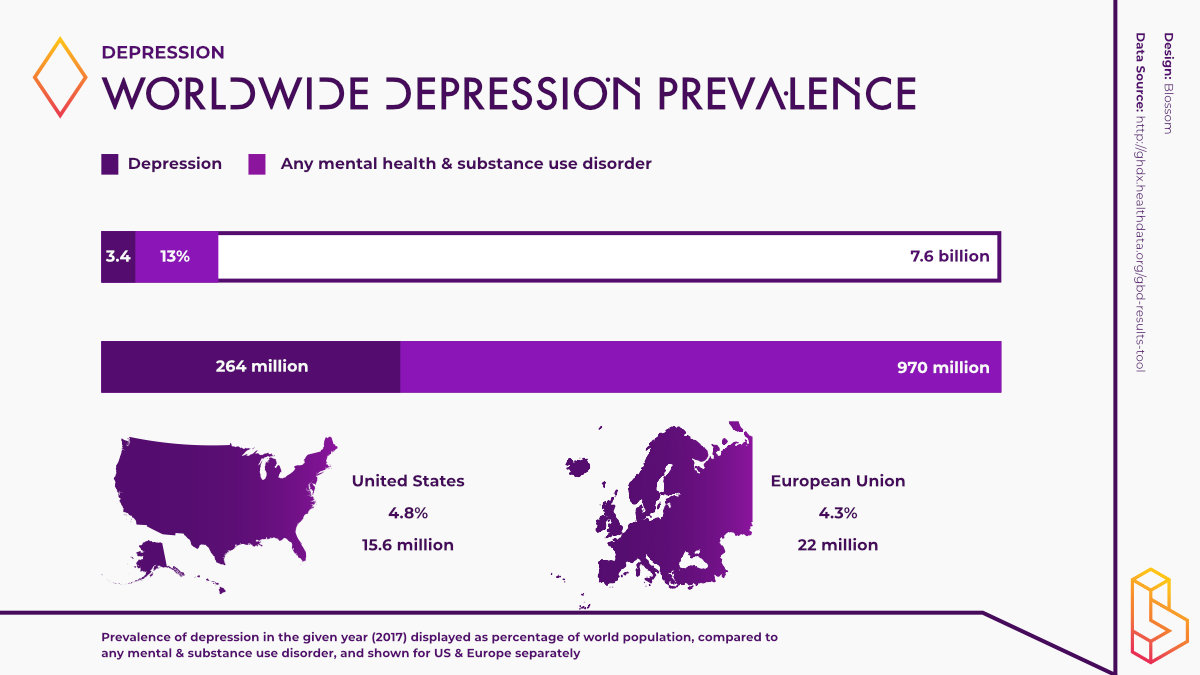

264 million people affected worldwide 1

Depression affects over 260 million people worldwide. This number is expected to be much higher as mental health disorders tend to underreported and are difficult to diagnose. Various forms of depression exist including treatment resistant depression as well as unipolar and bipolar depression. The prevalence of these disorders is believed to have significantly increased in wake the COVID-19 pandemic.

Current Treatments 1

Upon diagnosis with depression, a range of treatment options exist. Various forms of psychotherapy help to teach people to overcome any negative attitudes or feelings they may have including; cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT). Medication is often used in tandem with psychotherapy. Common medications include; SSRIs, SNRIs, TCAs and MAOIs. Unfortunately, many people remain unresponsive to medications and many produce unwanted side effects.

Psychedelic research currently is in Phase IIb

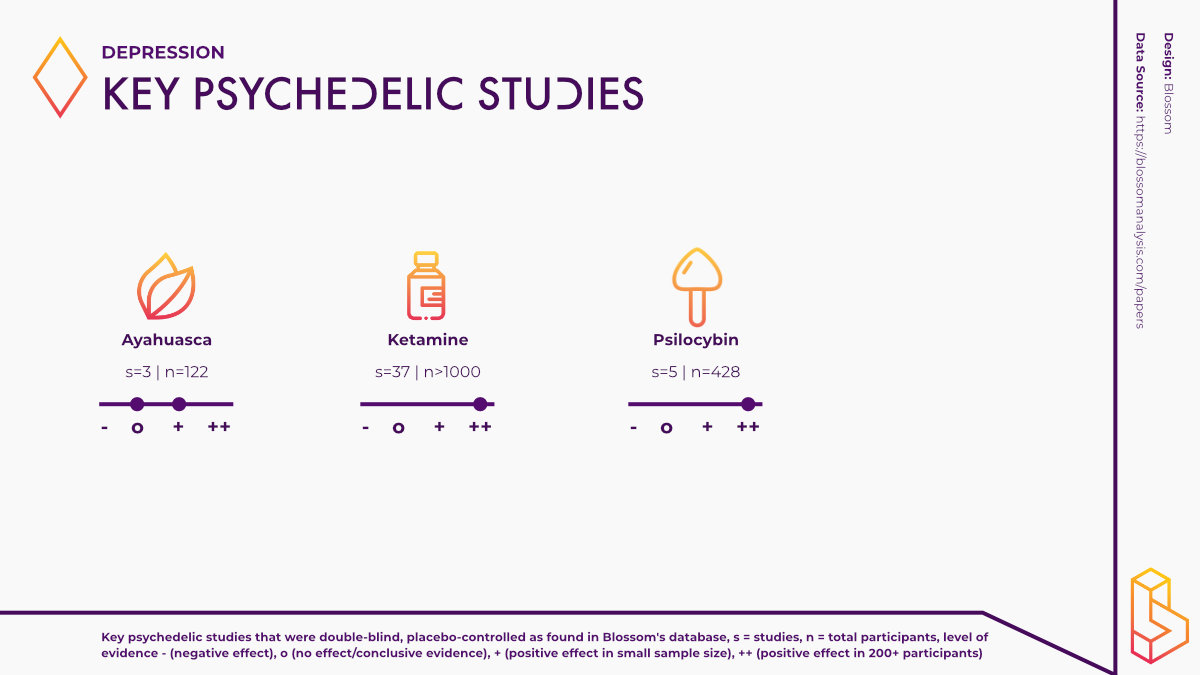

Out of all the disorders for which psychedelics hold promise, depression is perhaps the most extensively studied. Clinical trials using psychedelics such as; ketamine, psilocybin, ayahuasca and DMT are underway across the globe, with some Phase IIb trials nearing completion.

Get the extended version of this report.

🏢 Deeper analysis of companies working on this topic

📈 Market sizing & contextualization

🥼 Research stages (clinical trials) overview

Index of psychedelics for depression

What is depression?

Depression is a mental disorder that negatively affects how a person feels, thinks and acts. Also known as major depressive disorder (MDD), depression is characterised by persistent sadness and lack of interest or pleasure in previously rewarding or enjoyable activities and can lead to disruptions in sleep and appetite [1].

According to the DSM-V (a manual for assessment and diagnosis of mental disorders), symptoms of depression include; depressed mood, diminished interest or loss of pleasure in almost all activities, feelings of worthlessness, recurrent suicidal ideation, fatigue or loss of energy and psychomotor agitation, amongst others [2]. For depression to be diagnosed, at least five symptoms must be present during the same two-week period. While different forms of depression exist, such as bipolar depression and postpartum depression, they are covered in separate reports.

Depression severely limits a person’s ability to carry out day-to-day tasks such as work, family life or even meeting friends and partaking in social activities. Approximately 260 million people across the globe have depression, making it one of the most prevalent mental disorders [3]. Moreover, depression has been one of the highest causes of years lived with disability (YLD) for the past thirty years, representing a significant portion of the global disease burden [4].

Depressive symptomology and severity can vary from person to person, making it a difficult disorder to diagnose. Furthermore, although theories such as the monoamine hypothesis have been proposed, the exact physiological mechanisms which underlie depression remain contentious [5].

A number of diagnostic tools exist to aid medical professionals when diagnosing depression. These tools include the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). Although some tools are self-report measures, results are always reviewed by a medical professional.

Conventional treatment

Upon diagnosis with depression, a range of treatment options exist. Various forms of psychotherapy can help to teach people to recontextualise negative attitudes or feelings they may have. Typical forms of psychotherapy used are; cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT), psychoanalytic therapy, and interpersonal therapy.

In all forms of psychotherapy, medical professionals use verbal and psychological techniques to help them while fostering a strong patient-therapist relationship [6]. In most cases, psychotherapy is provided in conjunction with medications, of which there are many.

A range of antidepressant medications exist, each exerting its effects through unique physiological mechanisms. It is worth noting that antidepressants do not cure depression; instead, they reduce the symptoms. The type of antidepressant prescribed will depend on the patient’s personal circumstances and particular symptoms.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), like Prozac or Zoloft, act by increasing serotonin levels in the brain. SNRIs such as Cymbalta work similarly to SSRIs, except they increase levels of another neurotransmitter, norepinephrine, in the brain.

Other common classes of antidepressants include tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). While people benefit from medication, many remain unresponsive, and further limitations exist.

Firstly, many medications need to be taken daily for a prolonged period to exert their effects. Additionally, the FDA requires all antidepressants to carry ‘black box’ warnings, their most severe warning, given that some side effects may include increased suicidal ideation [7]. Making matters worse, the societal stigma associated with depression drives many people to hide it, try to tough it out, or misuse alcohol or drugs to get relief [8].

With conventional treatments for depression having somewhat limited efficacy and unwanted side effects, novel treatments are needed. Fortunately, psychedelics are re-emerging into society, bringing with them the serious potential to treat depressive disorders.

Psychedelics and depression

Out of all the disorders for which psychedelics hold promise, depression is perhaps the most extensively studied. Many of the clinical trials that have taken place or are underway focus on treatment-resistant depression (TRD). As the name suggests, people who have TRD do not respond to conventional treatments and therefore, there is an unmet need to help these people.

On the basis of the vast amount of preliminary clinical evidence available, even the FDA has recognised the potential of psychedelics to treat the unmet needs of those with major depressive disorder. In 2019, the FDA awarded ‘breakthrough therapy’ status to both esketamine and psilocybin for treating TRD. This designation helps to accelerate the drug development and review process, ultimately helping patients access these therapies as quickly as possible.

Across the globe, researchers are at various stages of the drug development process exploring the potential of a whole range of psychedelics to treat depressive disorders, largely showing great promise in small trials.

Ketamine

In 1970, ketamine was approved for use as an anaesthetic by the FDA. Unlike other anaesthetics, ketamine doesn’t slow breathing or heart rate and therefore, can be used with the need of a ventilator [10].

Ketamine doesn’t fall into the category of classic psychedelics, rather it is a dissociative meaning it distorts one’s perception of sight and sound and produces feelings of detachment from the environment and/or self [10]. Medical professionals began to notice that this dissociative state may be of therapeutic value for mental disorders.

It wasn’t until the early 2000s that researchers began exploring the potential antidepressant effects of ketamine in a double-blinded, randomized controlled trial [11]. Given that ketamine is easily accessible when compared to other psychedelics, research has flourished in the past years.

Two main types of ketamine are used to treat depression; arketamine and esketamine. Racemic ketamine (ar/es-ketamine) is currently being used off-label to treat depression. This form of ketamine is a mixture of both the “R” and “S” ‘handedness’ of ketamine molecules is often administered intravenously.

The latter, esketamine, is given as nasal spray and its manufacturers Janssen Pharmaceuticals have been awarded FDA approval to sell this form under the brand name Spravato.

It is believed that ketamine exerts its therapeutic effects by binding to NMDA receptors in the brain, increasing levels of the neurotransmitter glutamate. Glutamate then activates AMPA receptors which, in turn, promotes synaptogenesis and likely affects mood, thought patterns, and cognition [12].

One of the main beneficial effects of ketamine, when compared to other antidepressants, is its ability to rapidly alleviate symptoms of depression. Recently, the ASPIRE I and ASPIRE II studies demonstrated that esketamine can rapidly reduce symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder with active suicidal ideation with intent. A pooled analysis of these Phase III trials can be found here.

These findings demonstrate rapid and robust efficacy of esketamine nasal spray in reducing depressive symptoms in severely ill patients with major depressive disorder who have active suicidal ideation with intent.

Fu et al. 2020

This open-label study found that the effects of repeated ketamine infusion persisted for 18 days, which is in agreeance with the current literature.

Although the effects may not be long lasting, the speed at which ketamine acts is of particular use, particularly in patients who are depressed and have accompanying suicidal ideation. The exact long-term effects of repeated ketamine doses still have to be thoroughly investigated. However, given the legal medical status of ketamine, it is a widely available treatment option. A plethora of clinics offering ketamine-assisted therapy exist in the U.S and some in Europe.

Psilocybin

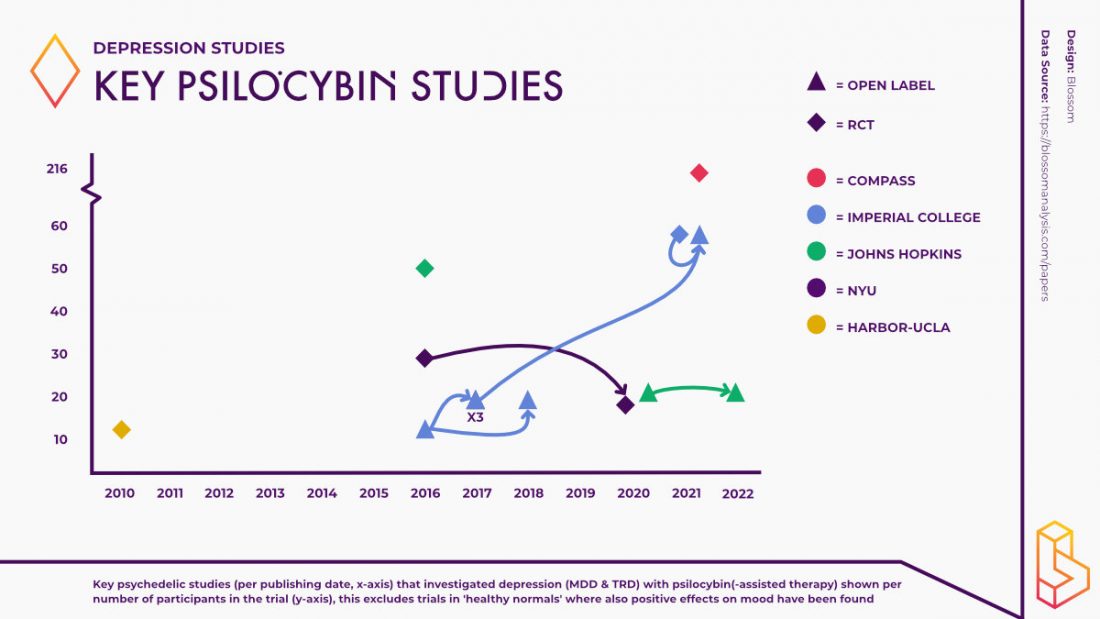

One of the first studies exploring the effects of psilocybin for the treatment of people with depression took place in 2016 at Imperial College London. Led by Dr Robin Carhart-Harris, this open-label feasibility study demonstrated that psilocybin along with psychological support can reduce depressive symptoms over periods of one week to three months after treatment, with no serious adverse effects.

A 6-month follow-up study found the antidepressant effects incurred by participants remained significant. Since then, researchers have been exploring the potential of psilocybin to treat depression across the globe.

At Johns Hopkins, the research team found that two psilocybin-assisted therapy sessions produced a long-lasting (up to 8 weeks) reduction in symptoms in those with major depressive disorder.

At the 12-month follow-up, a durable antidepressant effect was observed with treatment response (⩾50% reduction in GRID-HAMD score from baseline, Cohen d = 2.4) and rate of remission at 75% and 58%, respectively, at 12 months. No serious adverse events related to psilocybin were observed.

Recently, Dr Carhart-Harris led a double-blind placebo-controlled study comparing psilocybin to escitalopram, a common SSRI used to treat depression. Although the researchers found no significant difference between the psilocybin group and the control group on their main measure of depression (QIDS-SR16), the study did find significant differences, favouring psilocybin, on the HAM-D-17 and the MADRS.

Although limited conclusions can be drawn about treatment efficacy from open-label trials, tolerability was good, effect sizes large and symptom improvements appeared rapidly after just two psilocybin treatment sessions and remained significant 6 months post-treatment in a treatment-resistant cohort.

Carhart-Harris et al. 2017

Many more trials are underway investigating the efficacy of psilocybin for treating various aspects of depressive disorders. Perhaps the largest of these trials is being undertaken by COMPASS Pathways, using their synthetic derivative of psilocybin. They have conducted a randomised controlled Phase IIb study of psilocybin therapy with 233 patients with treatment-resistant depression in 22 sites across Europe and North America, the largest Phase IIb study using psychedelics to date.

Recently, COMPASS published the preliminary findings from this study. It was found that a single dose of psilocybin (25mg) administered in conjunction with psychological support led to a statistically significant treatment difference of -6.6 points on change from baseline in MADRS total scores when compared to the control group. Moreover, the 25mg group demonstrated statistically significant efficacy from the day after the COMP360 psilocybin administration.

In spite of these positive results, a number of serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported. A total of 12 patients reported SAEs including; suicidal behaviour, intentional self-injury, and suicidal ideation at least one month after psilocybin administration. Such findings cannot be overlooked in light of the positive effects psilocybin-assisted therapy had on depression scores. For treatment models using psychedelics to become viable therapy options, we must fully understand the positive as well as the negative effects of these treatments.

Numerous studies have taken place in order to determine how psilocybin may alleviate the symptoms of depression, many of which are utilizing modern neuroimaging techniques. Using fMRI, Carhart-Harris and colleagues found changes in brain connectivity after psilocybin-assisted treatment in patients with treatment-resistant depression.

It has been postulated that psychedelics have the ability of psychedelics to alleviate symptoms related to serotonergic signalling in the brain’s default mode network (DMN) [13]. The DMN is a collection of pathways that govern our self-image, our autobiographical memories, and our deeply ingrained beliefs and thought patterns [14]. By reducing activity in this brain region, psychedelics allow people to alter the engrained beliefs which may be underlying their depressive symptoms.

In all studies, the importance of the psychotherapy aspect is emphasized. Patients need to prepare for the psychedelic experience, all while integration sessions are needed afterwards to make sense of the experience and gain the full therapeutic benefit.

As psychedelics may ‘turn off’ the DMN, the post-psychedelic experience integration session allows patients to more easily address and alter the thought patterns underlying their depression. This period of increased psychological flexibility is considered an important mediator of the therapeutic effects of psychedelic drugs, although further research is needed for definitive evidence [15].

LSD

During the first wave of psychedelic research in the 1950s and 1960s, psychedelics were being used to treat a range of disorders. James Rucker and colleagues (2016) provide a comprehensive review of psychedelics, namely lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), being used to treat unipolar mood disorders during this era.

The authors found that out of 423 participants across 19 studies, depressive symptoms were improved in 80% of patients. While the methodological standards of this era would not pass today, researchers have renewed interest regarding the potential of LSD to treat depressive disorders.

One reason why there is more research being done with psilocybin, next to the shorter duration, is that LSD still contains a lot of (counter) cultural baggage and thus will be less likely to be approved for research, with psilocybin being a more ‘sciency’ sounding name with fewer connotations.

In spite of this, some modern research has taken place using LSD to treat mental health disorders. Peter Gasser and colleagues (2014) found that when administering LSD (200μg) to patients with end-of-life anxiety, the significant anxiolytic effect of LSD were found to be similar to the studies secondary measures; depression. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was used to measure both anxiety and depression in this study.

Ayahuasca

Ayahuasca is a relatively well-studied compound that is showing efficacy when it comes to alleviating the symptoms of depressive disorders. This psychoactive brew has been used ceremonially by indigenous communities across Central and South America for centuries. Today, people from across the globe travel to ayahuasca retreats in search of the therapeutic benefits this plant possess.

An open-label study found that participants in these retreats reported improved scores of mental health parameters including depression, anxiety and self-compassion. In this study, 77% of participants who were depressed before the retreat, were no longer depressed directly after or at 6-month follow-up. While such findings are positive, participants were self-selected and there was no control group.

A retrospective survey study found that ayahuasca improved specific depressive symptoms (CESD-10) namely hope, depressed mood, and happiness.

In another open-label study, researchers found that a single dose of ayahuasca had significant antidepressant effects (measured using the HDRS and BDI, among others) which lasted up to 21 days.

Administration of ayahuasca was associated with rapid and sustained antidepressive effects. Results were similar across volunteers, regardless of the severity of the current depressive episode.

Faria Sanches et al. 2016

In 2019, Fernanda Palhano-Fontes and colleagues conducted a randomized placebo-controlled trial to explore the effects of ayahuasca in those with treatment-resistant depression. Although improvements in depression were similar in both the ayahuasca and placebo groups initially, the study found a significantly higher response rate in the ayahuasca group after a week.

Further analysis of these findings by Richard Zeifman and colleagues found that ayahuasca shows potential as a fast-acting innovative treatment for suicidal ideation.

Several studies have investigated how ayahuasca may exert its therapeutic effects on those with depression, although the exact pharmacology remains unclear. A double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trial observed a link between changes in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) serum levels and the antidepressant effects of ayahuasca. BDNF is a protein that has been shown to increase in levels after treatment with classical psychedelics like ayahuasca and LSD.

A similarly designed study explored the influence of ayahuasca on inflammatory biomarkers in those with treatment-resistant depression. Researchers found reductions in the concentration of C-reactive protein 48 hours after treatment and this may relate to the observed improvements in the patient’s depressive symptoms.

In a separate study, researchers found that a single dose of ayahuasca increased patients cortisol response to levels similar to healthy controls. These findings indicated another method through which ayahuasca may exert its antidepressant effects as cortisol plays a role in regulating emotional and cognitive processes related to the causes of depression.

DMT

Dimethyltryptamine (DMT), one of the psychoactive components of ayahuasca, is also being investigated separately for its therapeutic potential regarding the treatment of depression. Although many anecdotal reports exist surrounding the benefits of using DMT, few clinical trials have taken place to determine these effects.

Nonetheless, Small Pharma working in collaboration with Imperial College London, received regulatory approval in the UK for the world’s first trial testing the efficacy of DMT for major depressive disorder. The Phase I/IIa trial will determine the safety and efficacy of DMT in a small number of patients. Small Pharma has recently announced the preliminary findings from the Phase I arm of this dose-escalating, placebo-controlled study.

A total of 32 healthy psychedelic naïve volunteers, across four dose cohorts, received either SPL026 (their intravenous DMT formulation) in combination with psychotherapy (n=24) or placebo (n=8). The preliminary results indicate that SPL206 is well tolerated and can be safely administered as no serious adverse events were reported while minimal, short-lived adverse events were reported on dosing day.

Another DMT compound under investigation is for the treatment of depression is 5-MeO-DMT. A survey study (n=362) found that 5-MeO-DMT used in a naturalistic group setting is associated with unintended improvements in both depression and anxiety.

Dublin-based, GH Research, has recently announced the results of a phase I trial with their 5-MeO-DMT formulation (GH001). In the trial, seven out of eight patients with TRD were in remission at day seven after dosing. GH001 was well-tolerated, without serious adverse events reported.

Implementation

A number of companies are hoping to harness the potential of psychedelics to treat depression. One of the most prolific companies in this space is the aforementioned COMPASS Pathways which is actively conducting clinical trials across the world using psilocybin to treat depression.

The London-based company was awarded breakthrough therapy status by the FDA for its psilocybin therapy for treatment-resistant depression. Specifically, COMPASS has developed a synthetic version of psilocybin called COMP360 which they are using in their clinical trials.

Recently, COMPASS was granted patents in the US for this specific molecule. COMPASS is collaborating with institutions from all over the world to realize the therapeutic potential of COMP360. Furthermore, COMPASS is collaborating with another well-known company in the world of psychedelics, atai Life Sciences.

atai is working towards using psychedelics to treat a number of disorders, one of which is treatment-resistant depression. As well as working with COMPASS and their COMP360 molecule, atai is also trialling other psychedelics including Salvinorin A, DMT as well as arketamine for the treatment of depression.

Through their Perception Neuroscience subsidiary, atai is developing PCN-101 (arketamine) for the treatment of depression and should be starting Phase II trials in the near future. From their Viridia Life Sciences subsidiary, atai is developing DMT in conjunction with digital therapeutics to help patients with treatment-resistant depression. The Berlin-based company has many other compounds in their pipeline for treating various disorders such as opioid use disorder, PTSD and generalized anxiety disorder.

Field Trip Health recently announced they have chosen treatment-resistant depression and postpartum depression as the target disorders for their molecule FT-104, a synthetic derivative of psilocybin. Similar to psilocybin, FT-104 is a 5HT2A receptor agonist although its psychoactive effects are expected to be much shorter in duration. Field Trip currently offers ketamine-assisted therapies for depression, amongst other mental health disorders, at its clinics across North America.

Novamind is similarly building a network of treatment clinics that currently work with ketamine (and esketamine) for (treatment-resistant) depression. With eight clinics and a research division (Cedar Clinical Research), Novamind is one of the places that is currently putting the research into practice.

Toronto-based PharmaTher is developing KETABET, a wearable patch that administers ketamine safely and conveniently in order to treat those with treatment-resistant depression. At present, trials exploring KETABET are in Phase I/IIa.

Overall, with the volume of work being done in this particular area of psychedelic science, it shouldn’t be long before people with depression can reap the benefits of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy and for many people, treatment-resistant depression becomes a thing of the past.

Download the extended version of this report. Available to our paying members.

🏢 Deeper analysis of companies working on this topic

📈 Market sizing & contextualization

🥼 Research stages (clinical trials) overview

References

1. World Health Organization. (2021). Depression. Geneva: World Health Organization. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression

2. American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Depression – Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. American Psychiatric Association. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519712/table/ch3.t5/

3. Dattani, S., Ritchie, H., & Roser, M. (2018). Mental Health. Our World in Data. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/mental-health

4. HME. (2021). Global Health Data Exchange. Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation. Retrieved from http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool?params=gbd-api-2019-permalink/d780dffbe8a381b25e1416884959e88b

5. Hirschfeld, R. (2000). History and evolution of the monoamine hypothesis of depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 4-6. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10775017/

6. Schimelpfening, N. (2020). 6 Types of Psychotherapy for Depression. VeryWell Mind. Retrieved from https://www.verywellmind.com/types-of-psychotherapy-for-depression-1067407

7. Drugwatch. (2020). Black Box Warnings. Drugwatch. Retrieved from https://www.drugwatch.com/fda/black-box-warnings/

8. WebMD. (2019). Understanding Depression – Diagnosis and Treatment. WebMD. Retrieved from https://www.webmd.com/depression/guide/understanding-depression-treatment

9. Collins, S. (2021). Ketamine for Depression: What to Know. WebMD. Retrieved from https://www.webmd.com/depression/features/what-does-ketamine-do-your-brain

10. Alcohol and Drug Foundation. (2021). Dissociatives. Alcohol and Drug Foundation. Retrieved from https://adf.org.au/drug-facts/dissociatives/

11. Berman, R., Cappiello, A., Anad, A., Oren, D., Heninger, G., Charney, D., & Krystal, J. (2000). Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biological Psychiatry.

12. Meisner, R. (2019). Ketamine for major depression: New tool, new questions. Harvard Health. Retrieved from https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/ketamine-for-major-depression-new-tool-new-questions-2019052216673

13. Mason, N. L., Kuypers, K. P. C., Reckweg, J. T., Müller, F., Tse, D. H. Y., Da Rios, B., … & Ramaekers, J. G. (2021). Spontaneous and deliberate creative cognition during and after psilocybin exposure. Translational psychiatry, 11(1), 1-13.

14. Buckner, R., Andrews-Hanna, J., & Schacter, D. (2008). The brain’s default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1-38. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18400922/

15. Davis, A., Barrett, F., & Griffiths, R. (2020). Psychological flexibility mediates the relations between acute psychedelic effects and subjective decreases in depression and anxiety. Journal of Contextual Behavioural Science.

Highlighted Institutes

These are the institutes, from companies to universities, who are working on Depression.

McGill University

Psychedelic research is well underway at McGill University. At the Neurobiological Psychiatry Unit, researchers are assessing the effects of psychedelics at the behavioral, brain circuit, neuronal, and subcellular levels.

Canadian Rapid Treatment Centre of Excellence

Established in 2018 the Canadian Rapid Treatment Centre of Excellence offers ketamine therapy to aid those suffering from several treatment-resistant conditions such as depression and bipolar disorder.

EI.Ventures

EI.Ventures is a subsidiary of Orthogonal Thinker that is currently raising $50 million. Though scant on details, the company is developing Psilly (whole-plant botanical psilocybin-based formulation) and has (presumably) launched a consumer non-psychedelic mushroom brand 'Mana'.

Revixia Life Sciences

Revixia Life Sciences is a biotech company developing Salvinorin A (salvia) for substance use disorders (SUD), treatment-resistant depression (TRD), and pain.

ATAI Life Sciences

atai Life Sciences is one of the biggest companies in the psychedelics field. The company aims to be a platform and has nine subsidiary companies working on everything from psilocybin for depression to DMT administration.

Compass Pathways

COMPASS Pathways is a publicly listed company (NASDAQ) that is developing psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression (TRD) for which it has completed a successful Phase IIb trial. COMPASS is one of the largest psychedelic companies and has received substantial investment from atai.

Pharmather

Pharmather is a Canadian life sciences listed company that is developing psychedelics for brain and nervous system disorders.

Viridia Life Sciences

Viridia Life Sciences is a subsidiary of ATAI that investigates DMT and the possible administration of it.

Perception Neuroscience

Perception Neuroscience is a subsidiary of atai that is developing arketamine therapy for neuropsychiatric diseases.

Imperial College London

The Centre for Psychedelic Research studies the action (in the brain) and clinical use of psychedelics, with a focus on depression.

Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Medicine) is host to the Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research, which is one of the leading research institutes into psychedelics. The center is led by Roland Griffiths and Matthew Johnson.

Johnson & Johnson

One of the largest pharmaceutical companies in the world, Johnson & Johnson are responsible for bringing esketamine to market in the form of Spravato.

Small Pharma

Small Pharma works on the development of two drugs. Together with Imperial College London they are developing intravenous administration DMT. The other project is a variant on ketamine (SPL801B).

Field Trip

Field Trip is a company that offers psychedelics therapies. It has several locations (US/CA) that provides ketamine-assisted therapy. It has raised $19.5M in Series A & B funding rounds.

Novamind

Novamind has bold plans for building out a psychedelic ecosystem. One that spans from ketamine-assisted psychotherapy and psilocybin retreats to novel clinical trials.

Highlighted People

These are some of the best-known people, from researchers to entrepreneurs, working on Depression.

Cristina Albott

Cristina Albott is a psychiatrist who treats patients in need of mental health care. She is currently leading a trial investigating the effectiveness of repeated ketamine infusions in veterans with PTSD and comorbid depression.

Madeline Li

Madeline Li is an Associate Professor in the Department of Psychiatry, University Health Network and a clinician-scientist in the Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care a the University of Toronto.

Pierre Blier

Pierre Blier is a Professor at the University of Ottawa, Department of Psychiatry and Cellular/Molecular Medicines and the recipient of the Endowed Chair in Mood Disorders Research at the University of Ottawa Institute of Mental Health Research (IMHR).

Joshua Rosenblat

Joshua Rosenblat is a psychiatrist and clinician-researcher at the Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit at the University of Toronto. He is also the Medical Director of the Canadian Rapid Treatment Centre of Excellence (CRCTE), Chief Medical & Scientific Officer of Braxia Scientific and co-founder of 1907 Research.

Rafael dos Santos

Rafael dos Santos is a postdoctoral fellow at the Graduate Program in Mental Health at the Faculty of Medicine of Ribeirão Preto (FMRP-USP), where he also works as an accredited advisor.

Declan McLoughlin

Declan McLoughlin is a Research Professor of Psychiatry at the Trinity Institute of Neurosciences (TCIN) in Trinity College Dublin.

Dulce Martinez

Dulce Maria Rascon Martinez is an Associate Professor in the Department of Anaesthesiology at the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social

Eric Lenze

Eric Lenze is the Wallace & Lucille Renard Professor of Psychiatry and the Director of the Healthy Mind Lab at Washington University School of Medicine. As part of his research, Lenze has explored the therapeutic effects of ketamine in older adults.

Mark Niciu

Mark Niciu is an Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Iowa. Mark and his team are interested in the therapeutic effects of ketamine.

Sanjay Mathew

Sanjay is a Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and the Director of the Mood and Anxiety Disorders Program at Baylor College of Medicine. He is currently exploring the use of ketamine in treating mood disorders.

Lou Lukas

Lou A. Lukas is a family medicine doctor in Omaha, Nebraska and is affiliated with Veterans Affairs Nebraska-Western Iowa Health Care System-Omaha. She is acting as the principal investigator in a study using psilocybin to treat psychological distress associated with cancer.

Anna Beck

Anna Beck is the Director of Supportive Oncology and Survivorship and an investigator at Huntsman Cancer Institute. She is the principal investigator on a trial using psilocybin in patients with cancer.

Joshua Woolley

Josh Woolley is an Associate Professor in Residence in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the UCSF. He is also the current Director of the Translational Psychedelic Research (TrPR) Program at UCSF.

Scott Irwin

Scott Irwin is the Director of the Patient and Family Support Program and Professor of Psychiatry & Behavioral Neurosciences at Cedars-Sinai. Dr Irwin has served as the principal investigator in numerous trials exploring the effects of ketamine on mental health issues in patients with cancer.

George Goldsmith

George Goldsmith is the CEO, Co-Founder, and Chairman of Compass Pathways, which he has led since July 2016.

Robin Carhart-Harris

Dr. Robin Carhart-Harris is the Founding Director of the Neuroscape Psychedelics Division at UCSF. Previously he led the Psychedelic group at Imperial College London.

Fernanda Palhano Xavier de Fontes

Fernanda Palhano Xavier de Fontes is a research engineer at the Brain Institute, UFRN. Her main areas of interest are psychedelics, psychiatry, and neuroimaging techniques such as fMRI and electroencephalography.

Richard Zeifman

Richard Zeifman is working at Imperial College London on psychedelics as a novel intervention for suicidality.

Linked Research Papers & Trials

Pro & Business members will be able to see all linked papers and trials directly on this topic page.

This information is still available for you by selecting Depression on the Papers and Trials pages respectively.

See the information directly on this page with a paid membership.