This column was written by Blossom’s founder Floris Wolswijk in cooperation, and co-published, with Lucid News

Psychedelics as therapeutic medicines have been studied for over half a century. MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD is on track to be approved in two years. Promising trials that study psychedelics as potential treatments for depression, anxiety, and addiction are ongoing.

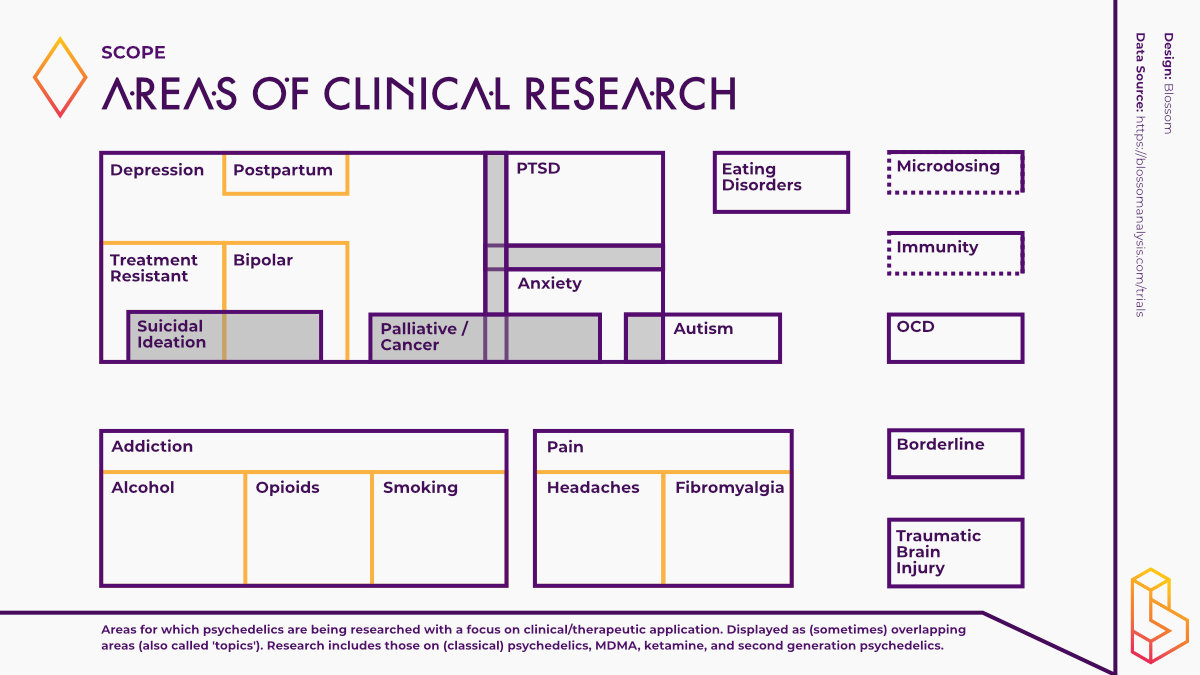

Open the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V, psychiatrists’ dictionary), pick any disorder, and you’re likely to see psychedelics research being conducted for it. Though psychedelic treatments for a few major indications get all the headlines, there are many more conditions for which psychedelic treatments are being investigated.

With the Interdisciplinary Conference on Psychedelic Research (ICPR) just behind us, I want to give you a peek into the underside of the iceberg of psychedelic research. Let’s step away from the headlines, broaden our scope, and dive into the frontier of this field.

The Four Horsemen of the DSM

Before we do that, let’s take a look at the current state of psychedelic research for PTSD, alcoholism, depression, and anxiety. Though some of the studies are reaching the finishing line (positive Phase III results), a long and arduous road is still ahead before receiving FDA approval.

MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD is currently the furthest along. MAPS PBC, the public benefit corporation wholly owned by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), expects to start treating patients in 2024. They are conducting the second part of a Phase III trial with over 200 participants to get FDA approval. A complementary Phase III study with 70 participants in Europe is happening in parallel, allowing the continent to follow with European Medicines Agency (EMA) approval in 2026.

This past August, Michael Bogenschutz and colleagues published the first double-blind study on patients with alcoholism. Patients received cognitive behavioural therapy and two high doses of psilocybin. When researchers followed up eight months later, they drank significantly less than those who received the placebo.

It took Bogenschutz’s team eight years to complete the study. Over that period, the psychedelic landscape has changed exponentially. Three more clinical trials are lined up this year to test psilocybin and LSD for alcoholism, and ibogaine is also studied for alcoholism and opioid addiction in regions outside the U.S.

The most well-studied mental health disorder with psychedelics is depression, with over a third of clinical trials investigating psychedelics designed to address depression. Psilocybin was the first psychedelic to be given a head-to-head comparison with a common antidepressant. Although no statistically significant difference was found in the main measure of depression, secondary results suggested psilocybin may be more effective.

The for-profit company Compass Pathways is the furthest along on the path to commercialisation. They have conducted a large-scale Phase IIb study with positive results. The results were less pronounced than in earlier academic studies – only one dose of psilocybin, instead of two to three, and relatively little supportive therapy were given.

The fourth disorder that has been studied extensively is anxiety. Studies on anxiety related to end-of-life in cancer patients arguably played an integral role in the resurgence of psychedelic research. In 2010, Charles Grob and colleagues published a 12-person study in which patients with advanced-stage cancer treated with psilocybin found immediate relief from anxiety which lasted several months.

Researchers at the University of Basel recently conducted a double-blind study with a high dose of LSD, which also found significant reductions in anxiety.

The studies conducted by Grob and the University of Basel also showed a significant reduction in depressive symptoms in the treated patients. It highlights one crucial aspect of psychedelic-assisted therapy: improvements are seen across the board in more cases than not. Someone treated for PTSD may also drink less, have a healthier relationship with food, and feel less depressed.

The Forward Edge of Psychedelic Research

Psychedelic research showcases the potential for these substances to treat a wide scope of mental health disorders.

Outside of the big four, psychedelics are being researched for at least 18 other indications. These range from other mental health disorders, to pain disorders, and substance abuse issues (see the chart above for the full range of what psychedelics are currently being studied for.)

Here I focus on two pain disorders (fibromyalgia and headache), eating disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorders. Active research is taking place in these areas, and new findings are emerging.

Treating Complex Pain Disorders

Fibromyalgia is a condition that causes pain all over the body, along with fatigue, cramps, depression, and insomnia. Two per cent of adults in the US currently suffer from fibromyalgia.

Not much is known about how psychedelics work to address pain. Several survey studies generally show positive attitudes towards psychedelics. In 2021, Nicolas Glynos and colleagues found that 37% of survey participants who had used psychedelics to treat fibromyalgia reported benefits.

Julia Bornemann and colleagues at the Centre for Psychedelic Research at Imperial College London (ICL) are furthest in studying psychedelics for fibromyalgia. In preparation for an ongoing trial, they interviewed people who had used psychedelics to manage pain. Two processes stood out: Positive Reframing and Somatic Presence. The former describes a journey from pain catastrophizing towards acceptance and empowerment. The latter is a renewed mindfulness of physical experiences and physical catharsis.

This year, three clinical trials have begun to investigate the effect of psilocybin on fibromyalgia. At ICL, the first brain measures will be taken to explore how two doses of psilocybin influence the complexity of brain signals. A measure of complexity called Lempel-Ziv is hypothesized to be higher in those suffering from fibromyalgia. Psilocybin lowers this complexity, indicating a possible causal mechanism through which it works.

In the United States, two more trials investigate what psilocybin can do for fibromyalgia. A trial at the University of Alabama will be the first double-blind study, in which participants and researchers alike will not know who receives psilocybin or placebo. The first commercial study will be done by Tryp Therapeutics. All trials are expected to conclude by the end of 2024, and will treat 70 participants combined.

Busting Headache Disorders

For most people, headaches are a slight inconvenience. Take an aspirin, and the headache goes away. Unfortunately, this is not the case for one in seven people suffering from several headache disorders.

The most common is migraines, which usually last several hours and occur chronically. Other headache disorders include cluster headaches (also dubbed ‘suicide headaches’) and short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks (SUNHA), both of which come in shorter but more intense bouts.

Seven clinical trials are investigating the effects of psilocybin and LSD to abort and prevent further headaches. The completed studies show a 50% and 30% reduction in the frequency of migraines and cluster headaches, respectively. Though small in size (fewer than 50 participants have completed the studies) the data points toward a new avenue for treating headache disorders.

Emmanuelle Schindler and colleagues at Yale University have been most prolific in treating headache disorders with psilocybin. The clinical trials they conduct usually give participants multiple medium doses of psilocybin (up to 10mg – comparatively low as other studies usually dose up to 30mg) over multiple days or weeks.

Surprisingly, the intensity of the acute psychedelic experience doesn’t correlate with the reduction in headaches. This means that, in contrast to other studies, the acute effects of the trip don’t predict if someone will have fewer migraines or cluster headaches. If this remains true when more studies are done, it may confirm the suspicion some have that the anti-headache effects of psychedelics are distinct from the acute psychological effects. Similarly, a case series with six participants shows that the non-hallucinogenic psychedelic BOL (an LSD-like molecule) can positively affect headache frequency.

Though much data on psychedelics for headache disorders is based on surveys, more extensive trials are underway to tease out how and why psychedelics can work for headache disorders. Though far from a total solution – many participants still experience headaches after treatment – psychedelics offer a way forward for a significant number of people who lack other options.

Restoring the Relationship with Eating

Everyone has a relationship with food. For some, it’s fuel. For others, it’s a passion or profession. For over 16 million people, it’s a daily struggle.

People suffering from eating disorders have problems with eating and the thoughts and emotions associated with it. A disproportionate amount of those who suffer from it are women.

Among eating disorders, bulimia is the most prevalent, with four out of five experiencing bouts of overeating and purging. The second most prevalent is anorexia, which is characterised by restricted eating and low body mass index, and has the highest mortality rate of all psychiatric conditions.

The possibility of psychedelics helping with eating disorders was tested as early as 1959. A case study by French researchers reported positive findings in one woman with anorexia who received two injections of psilocybin. Modern research started 60 years later in 2019.

A total of seven clinical trials with over 150 participants examine the effects of psilocybin and MDMA on eating disorders. The modern-day research started at Johns Hopkins, where early reporting on their trial indicates that those with anorexia reported fewer psychological effects. Subsequent participants were then dosed with a whopping 30mg of psilocybin.

At Imperial College London, researchers use brain imaging techniques to help find the underlying mechanisms by which psychedelics can help. Unlike the headache trials, eating disorder trials like these employ talk therapy alongside psychedelic treatment.

MDMA-assisted therapy has also been shown to lower scores on an eating disorders measure in those being treated for severe PTSD. MAPS will test this hypothesis directly with 18 patients with anorexia and binge eating disorder in an open-label trial.

The biggest trial is being conducted by Compass Pathways, where 60 patients with anorexia will receive one 25mg dose of COMP360 (psilocybin). This trial will be the first one with blinding and a substantial number of participants, allowing statistical data to be collected.

Overcoming Compulsive Distractions – Psychedelics vs OCD

Before leaving the house for vacation, it’s not uncommon to repeatedly make sure the stove is off, the lights are out, and the front door is locked. For those suffering from obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), these recurring thoughts and ideas (obsessions) can drive them to take actions repeatedly (compulsions).

The brain mechanisms that instantiate obsessions involve a loop that runs between different brain areas. Though not everything is understood in detail, we know that the serotonin (5-HT) receptor is involved. Naturally, researchers asked if psychedelics can help those with OCD. In 1998, Francisco Moreno and his colleagues wondered if they could help the approximately 70 million people suffering from OCD.

A small trial with nine participants showed promising results. In the last few years, trials with a combined 120 patients have begun taking place at the University of Arizona, Yale, Johns Hopkins and the Beersheva Mental Health Center in Israel.

Unlike other psychedelic studies, all but the study in Israel have chosen not to combine drug sessions with therapy. Also uncharacteristic is the use of multiple dosings – up to eight high doses – in the ongoing trial in Arizona.

Not much is known about the long-term effects of psilocybin for OCD, the only psychedelic being studied, but early data points towards the effects lasting beyond the studied 24 hours. By the end of 2024, when most trials are finished, we should know more about the feasibility of psychedelics for OCD.

The Mind-Altering Scope of Psychedelic Research

The eight areas we’ve covered, from PTSD to OCD, are but the tip of the psychedelic iceberg. Over 10,000 participants are enrolled in clinical trials for the 22 categories we’ve identified. Even this is a sliver compared to the use of psychedelics outside of research settings, for personal growth and healing, spiritual pursuit, or recreational purposes.

Researchers hope that psychedelics can make life better for everyone dealing with ailments from nicotine addiction to postpartum depression. But lest we forget, psychedelics are no panacea.

Psychedelics don’t work for a third to half of the patients treated under the best circumstances. It would be remiss to expect a substance and therapy combination to solve the myriad societal problems underlying many of these health issues.

We can say that the study of psychedelics has unearthed connective threads that span across the neat psychiatry silos made by the DSM-5. A single compound shows effectiveness across tens of domains. This is true for psilocybin, MDMA, and will likely be so for the other psychedelics being studied. The wide range of psychedelic research being conducted is already showcasing the breadth and depth of psychedelics for health and well-being.

Become a psychedelic insider

Get a Pro Membership to enjoy these benefits & support Blossom📈 full reports on Topics & Compounds

🧵 full summary reviews of research papers

🚀 full access to new articles

See Memberships