Welcome to the annotated slides for a History & Outlook on Psychedelic Science.

Let me introduce myself, I’m Floris Wolswijk, founder of Blossom which has been providing information on psychedelic research for the past four years. Blossom is an insight engine, providing 90% of our information for free and helping those in the space with consultancy.

I’m a psychologist by study, studying at the Erasmus University Rotterdam and graduating with my Master’s degree in 2013.

I’m a psychonaut by participation and have taken psychedelics for over a decade.

As an entrepreneur, I know how to build resources people can use and have been doing so for psychedelics for the past four years. The plans with Blossom aren’t to become a billion-dollar company but to help progress the field to a quicker acceptance of psychedelics for those unwell and people using psychedelics recreationally.

The information on Blossom is powering this presentation.

I’ve worked together with these amazing companies in the psychedelic space. I’ve done so both in a volunteer (V) and paid (P) positions. For instance as a volunteer for the OPEN Foundation which organises ICPR every second year.

Next to the companies listed here, I’ve been a pro-bono or paid media partner for other psychedelic conferences.

I don’t hold any stocks, or bonds, or made pinky promises while in hyperspace (afaik).

In other words, although I’m a cheerleader for psychedelic science, I’m not beholden to anyone in the space.

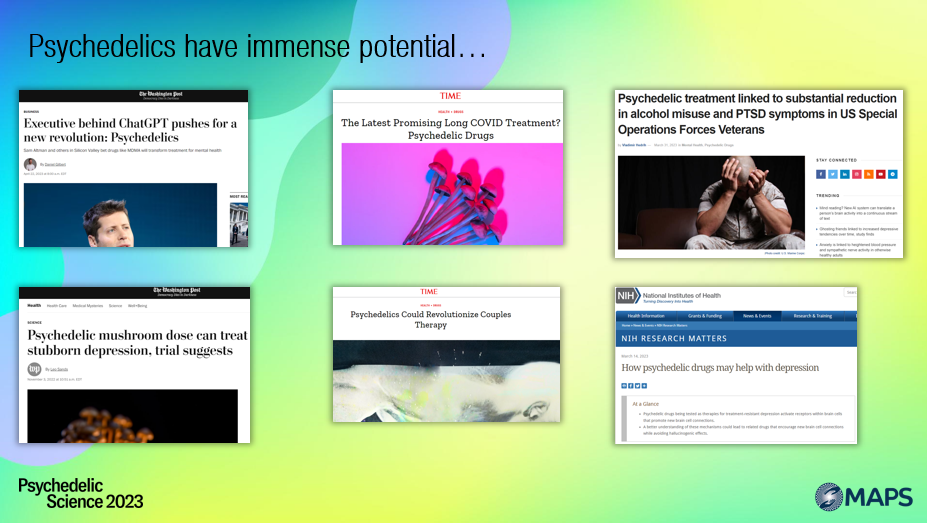

The thesis for this presentation is that psychedelics have immense potential …

We hear about them in news stories and are gathered here with 10.000 people to celebrate their medical, spiritual & societal benefits.

From treating depression & PTSD to couples therapy & long COVID symptoms, all signs point towards a bright future.

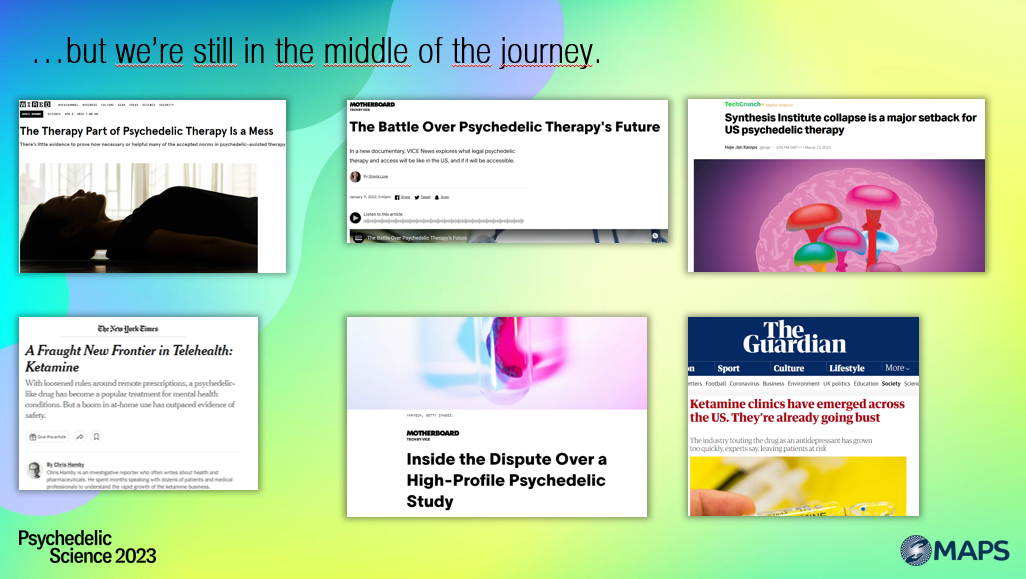

… but we’re still in the middle of the journey.

This trip hasn’t come to a satisfactory conclusion, we’re in the middle of the ups & downs of a journey.

What will psychedelic-assisted therapy (PAT) look like? How effective is ketamine really? And will this even become available to the everyday man or woman as a licensed therapy?

In this presentation, I’ll back up this ‘grounding’ statement before I release you all back into the bustle and hype.

Subscribe to The Bloom newsletter

A weekly email, sent on Tuesday (paid) or Thursday (free), packed with the latest

psychedelic research, news & actionable insights

I’m talking today specifically about the clinical – or medical – application of psychedelics. I recognize the centuries of indigenous use and that most psychedelic trips are recreational.

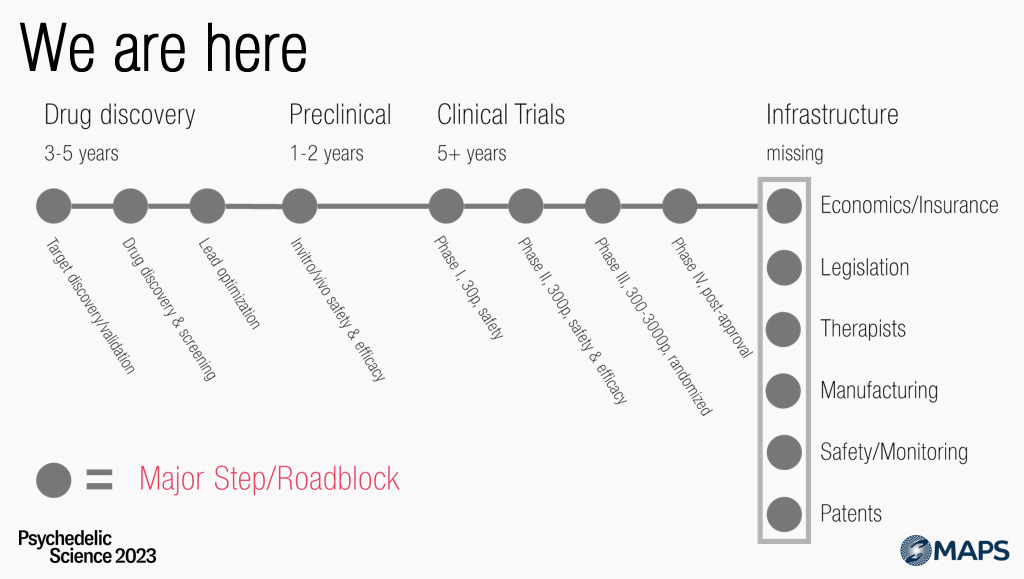

Within this narrow framework, this is a rough draft of a roadmap. Everything on the right side of the chart is in its infancy.

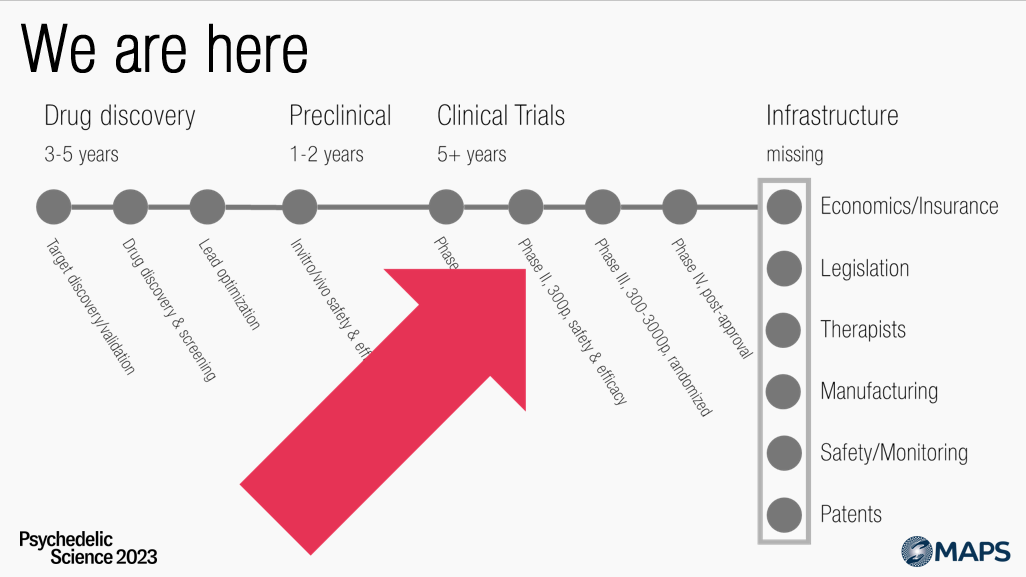

So, I want to argue, we aren’t even there, we are …

HERE

Firmly in the middle, the clinical trial process.

We know that existing psychedelics, like LSD, ayahuasca, psilocybin, and MDMA are generally safe.

But we – from a scientific lens – have no clue about the efficacy of psychedelics and have to find out through clinical trials.

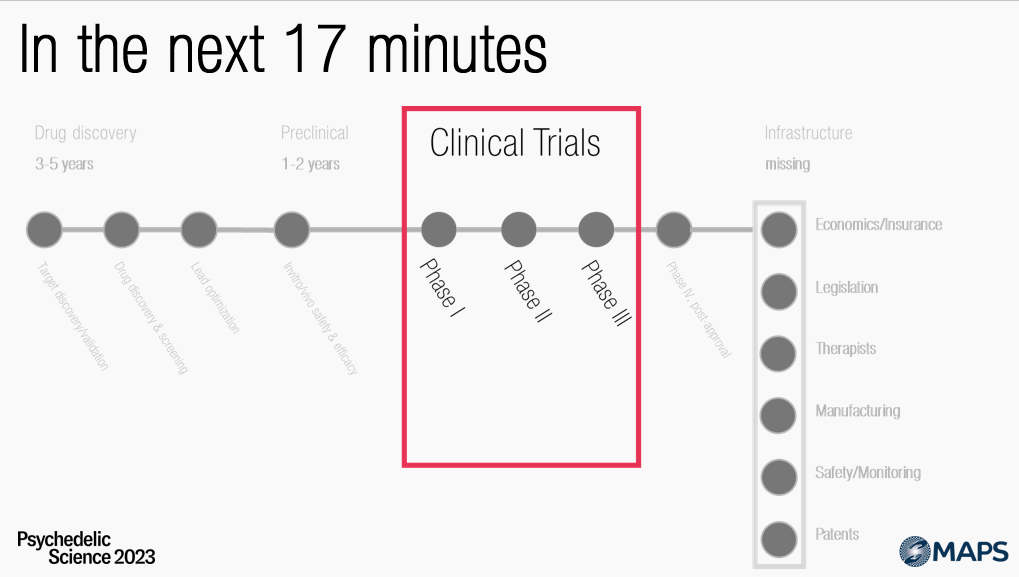

Clinical trials are fraught with difficulties – try and ‘double-blind’ psychedelic trials – and although I agree with much of the criticism on this point, I won’t further elaborate on that here.

As promised in the promo for this talk, I’ll take you on an 88-mph tour of the

- Past – everything up to 1990, incidentally when I was born

- Present – up to today

- Future – what I think the future of psychedelic research holds

But first, let me test your knowledge.

I have three questions for you. Let’s start with the first.

By a show of hands, “How many patients – not ‘healthy’ volunteers – have participated in completed psychedelic – this means LSD, MDMA, psilocybin, etc, but excludes ketamine – clinical trials?

Again, by show of hands, “Of ‘blinded’ studies – meaning usually half of the participants received a placebo – what percentage tested if the studies were double-blind? I.e. both researchers and participants didn’t know who received the active dose?

- Up to 25%; One in for or fewer asked

- Up to 50%; Half of the studies asked

- Up to 75%; Three out of four

- Up to 100%; Almost all of them

Then the third out of three questions, “How many Phase III trials – the pivotal studies before a medicine is approved – have been registered?

- 1-2

- 3-4

- 4-6

- 7+

Now that I’ve calibrated your expectations, let’s go back in history for a moment.

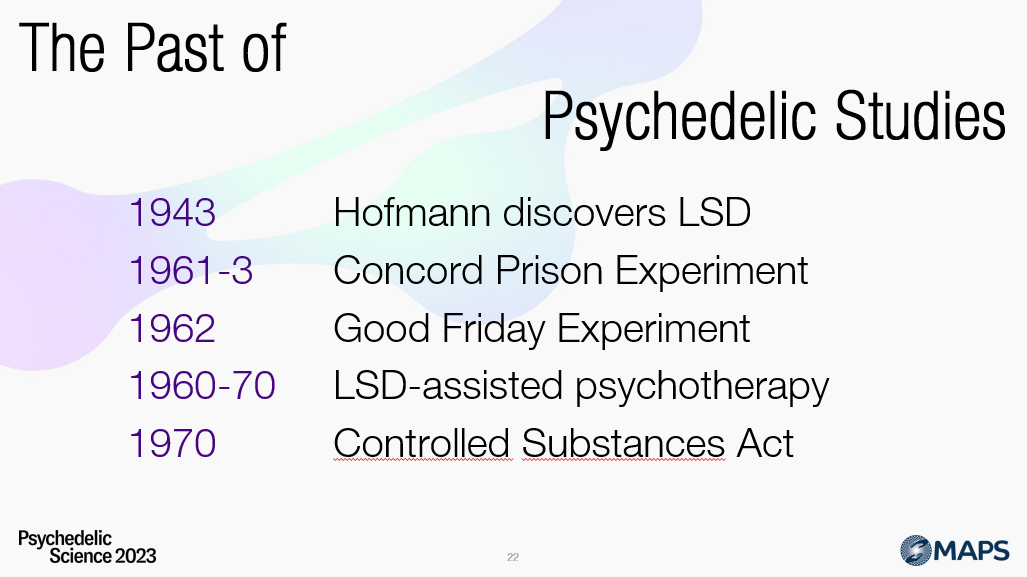

With that quiz behind us, let’s turn towards the past of psychedelic studies. I’ll briefly mention some of the pivotal points in clinical research from before my time.

Delving into the annals of psychedelic history, the story begins in 1943 with a Swiss chemist, Albert Hofmann, who serendipitously discovered LSD, an abbreviation for Lysergic Acid Diethylamide. The journey of this discovery and its subsequent implications are detailed in his book “LSD: My Problem Child“. This remarkable finding triggered a cascade of scientific curiosity, which led the Swiss pharmaceutical company Sandoz to widely distribute samples of LSD and psilocybin – the psychoactive compound found in magic mushrooms – to a vast array of researchers. Their criteria for dispatch were extraordinarily lenient by today’s standards; essentially, anyone expressing a credible interest received samples, resulting in thousands of these substances being disseminated.

Fast forward to the early 1960s, and an intriguing experiment unfolds at Concord Prison. Timothy Leary, a charismatic yet controversial figure, led a research project using psilocybin to assess its potential impact on reducing prison recidivism rates. Initial results suggested a significant reduction in re-offending, igniting a wave of optimism about the therapeutic potential of psychedelics. However, these results were disputed later by Ralph Metzner and Rick Doblin, who argued that methodological flaws undermined the findings’ credibility.

Parallel to this, another compelling study, the Good Friday or Marsh Chapel Experiment, was conducted in 1962 involving divinity students. Under the supervision of Leary and Richard Alpert (later known as Ram Dass), Walter Pahnke explored the impact of psychedelics on mystical experiences. The students’ results on the Mystical Experience Questionnaire (MEQ) were positive, suggesting profound and meaningful experiences. However, some students’ subsequent behaviour – such as uncontrolled wandering and erratic actions – raised ethical questions about the study.

The 1960s, while a pivotal time for psychedelic research, were also marked by a darker chapter. Unethical studies were conducted that involved administering psychedelics to children with disabilities, a practice that’s universally condemned today. During this period, LSD therapy started gaining traction, with psychologists like Stanislav Grof applying the drug within a psychoanalytical framework.

The burgeoning era of psychedelic research was abruptly halted in 1970 with the passage of the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) in the United States. This legislation classified substances like LSD and psilocybin as Schedule I drugs, indicating a high potential for abuse and no accepted medical use, effectively ceasing all research.

In retrospect, the early era of psychedelic research was a period of extraordinary exploration, with tens of thousands of patients treated and hundreds, if not thousands, of research articles written. However, it lacked the scientific rigour expected in contemporary research, with rigorous control groups, double-blind methods, and meticulous follow-up studies. It was a time of fascinating discovery and questionable ethics, which shaped the narrative of psychedelic substances for decades to follow.

This takes me to the current renaissance.

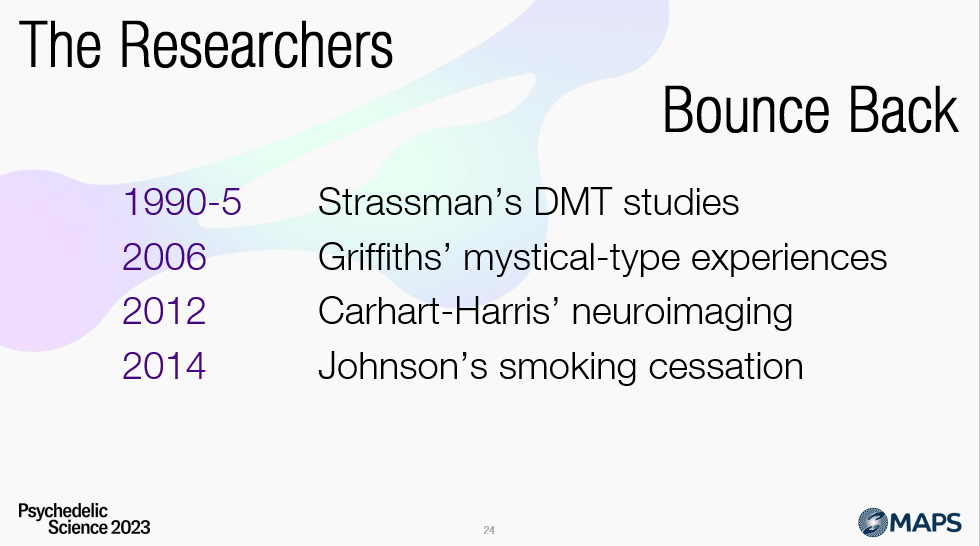

Studies never completely stopped, but research by Rick Strassman and colleagues, followed by Roland Griffiths and Robin Carhart-Harris has sparked a boom in psychedelic research not seen before.

Investigations with psychedelics look at how the brain works, and how these substances can help with various mental health and substance abuse disorders. And research like this has – from my perspective – laid the groundwork for us all to be gathered here today.

In the early 1990s, Dr. Rick Strassman led a research team that set out to explore the impacts of the potent psychedelic substance DMT on healthy volunteers. Over a five-year span from 1990 to 1995, the team meticulously observed and recorded the experiences of their participants, seeking to understand how DMT affects the human mind and consciousness. The results were nothing short of astounding. The volunteers reported profound, full-on mystical experiences that ranged from breathtaking visions to deeply insightful and introspective journeys into the self. These studies underscored the extraordinary potential of DMT to facilitate powerful shifts in personal perspective and understanding, opening up new areas of inquiry in the realm of psychedelic research.

Fast forward to 2006, a team of researchers at Johns Hopkins University, led by Roland Griffiths, demonstrated the remarkable power of psychedelics beyond the purely mystical. The study participants reported some of the most profound and meaningful experiences of their lives while under the influence of these substances. These weren’t fleeting moments of insight, either. The positive effects, including heightened self-awareness, improved interpersonal relationships, and increased life satisfaction, were sustained over extended periods, often lasting for many months after the psychedelic experiences. This landmark study provided an exciting indication of the transformative potential of psychedelics for personal growth and mental well-being.

In 2012, another crucial piece of the psychedelic puzzle began to emerge. A team of researchers, including Robin Carhart-Harris and David Nutt, delved deeper into the neuroscience behind the psychedelic experience. They focused on the intricate dynamics within the brain while under the influence of psychedelic substances. Their studies showed a reduction in top-down control – the usual dominance of conscious, analytical thinking – and an increase in more bottom-up processing, which is associated with subconscious and intuitive thought. This shift in brain function suggested a mechanism for how psychedelics might be helping individuals dealing with depression, alcoholism, and other mental health challenges, by loosening the grip of rigid thought patterns and allowing a more fluid, creative mode of cognition.

Further strengthening the case for the therapeutic potential of psychedelics, a 2014 study by Matthew Johnson and his team delved into the effects of psilocybin – the active compound in ‘magic mushrooms’ – on smoking cessation. The results were stunning. The influence of psilocybin therapy on smoking addiction surpassed even the most effective conventional treatments, including extended therapy and nicotine patch combinations. What’s more, these effects persisted even years later. While the initial study only included a small number of participants, the striking outcomes were compelling enough to attract federal funding for follow-up research.

In summary, each of these studies marked significant milestones in the journey of understanding the therapeutic potential of psychedelics. From profound mystical experiences to tangible, positive life changes, and neuroscientific insights into their potential as mental health treatments, psychedelics have emerged as a compelling area of research and therapy.

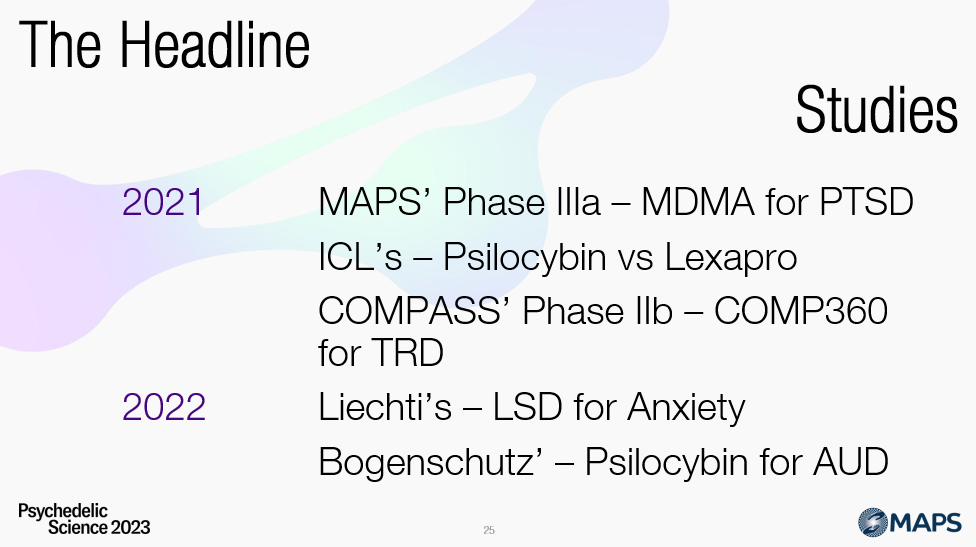

In recent years, groundbreaking research has been conducted in mental health, particularly exploring unconventional therapeutic agents. Some of these studies have sparked both academic and popular interest, given their profound implications for understanding and treating various mental health conditions.

In 2021, a significant announcement came from the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS). They revealed the encouraging outcomes of their study concerning MDMA-Assisted Therapy (MDMA-AT) for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). The results suggested that two-thirds of the subjects administered MDMA-AT no longer met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD after the treatment. This development demonstrated the potential efficacy of MDMA as a therapeutic tool, suggesting a new avenue for PTSD treatment that could revolutionize the way the condition is managed.

Simultaneously, a team of researchers from the Imperial College London (ICL) performed the first comparative study between a psychedelic substance, psilocybin, and a commonly prescribed antidepressant, escitalopram (marketed as Lexapro). The study sought to determine the relative efficacy of these two substances in treating depressive symptoms. While most secondary measures seemed to indicate that psilocybin was the superior treatment option, it’s important to highlight that no significant difference was found in the main measure of depression. The study’s results were deemed important enough to be published in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), signifying the growing acceptance and interest in the therapeutic potential of psychedelic substances within the scientific community.

Lastly, in 2022, two separate Phase II studies made significant strides in proving the efficacy of psychedelics for mental health treatment. One study by Matthias Liechti and colleagues demonstrated that Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD) effectively treats anxiety. This supports the growing body of evidence that proposes LSD as a potential therapeutic agent for anxiety disorders, a condition affecting millions of people worldwide.

The second study, by Michael Bogenschutz and colleagues, illustrated the potential of psilocybin as a treatment for alcoholism. With alcoholism being a widespread issue that is often resistant to conventional treatment methods, the suggestion that psilocybin could be used as a novel approach to treatment could be a game-changer in the field.

These studies, while preliminary, highlight the emerging paradigm shift in our approach to mental health treatment. They hint at a future where once stigmatized psychedelics may become mainstream therapeutic tools, presenting new hope for patients who have not found relief through conventional treatments.

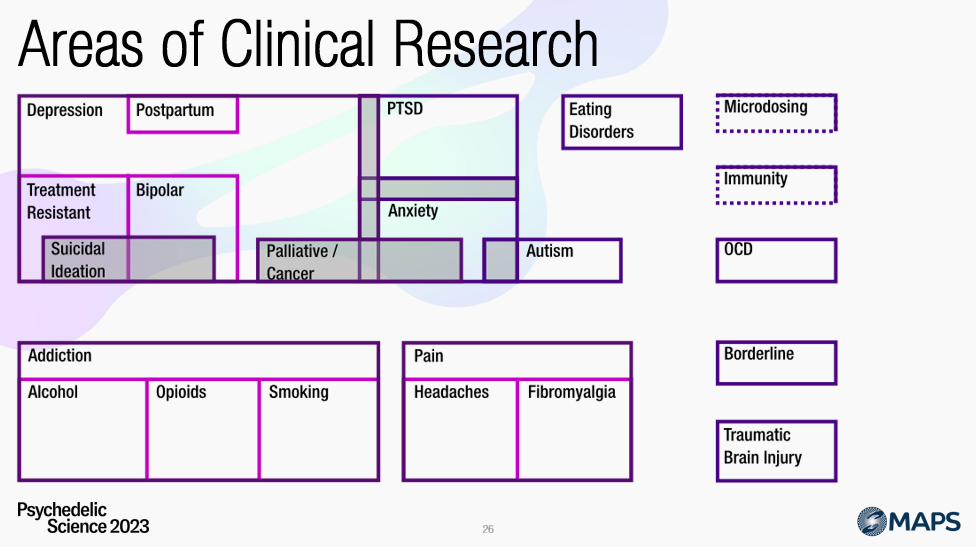

Psychedelics, once confined to the fringes of society and scientific research, are increasingly emerging as a promising frontier in mental health, addiction, and pain disorders. This remarkable shift has been fueled by rigorous and scientifically-sound studies investigating the therapeutic potential of these substances, which include classical psychedelics like psilocybin and LSD, along with MDMA, ketamine, and a new breed of substances known as second-generation psychedelics.

While most of this research is currently in Phase I, which assesses a new drug or treatment’s safety, dosage, side effects, and how it affects the human body, the early findings prove very promising. Many studies suggest that combining psychedelics and therapy might be superior to conventional treatments in addressing a broad spectrum of disorders. These potential applications span from depression, anxiety, and PTSD, to addiction issues, and even certain pain disorders. The wide range of therapeutic uses suggests psychedelics’ potential to revolutionize the mental health and addiction treatment landscape.

Given the breadth of this field, it’s understandably challenging to delve into the specifics of each study within a limited timeframe. However, for those interested in further exploring this burgeoning area of research, comprehensive reports on these subjects are freely available here on Blossom (use the top menu for diving in deeper). Each report links to all of the research articles for each area or topic, providing a wealth of information for curious minds.

The data presented here, derived from our trials database, provides a snapshot of the areas where psychedelics are being intensely researched for their clinical and therapeutic applications. The visual depiction presents these areas as overlapping ‘topics’, indicating that the potential benefits of psychedelics often transcend neatly defined boundaries of specific mental health, addiction, and pain disorders.

Revisiting the data from the first quiz question, it’s clear that the landscape of psychedelic research is expansive and nuanced. The emerging insights underscore the potential of psychedelics to address some of our most pressing health challenges. As the research progresses, we will likely see an ever-evolving understanding of these substances’ role in promoting mental health and well-being.

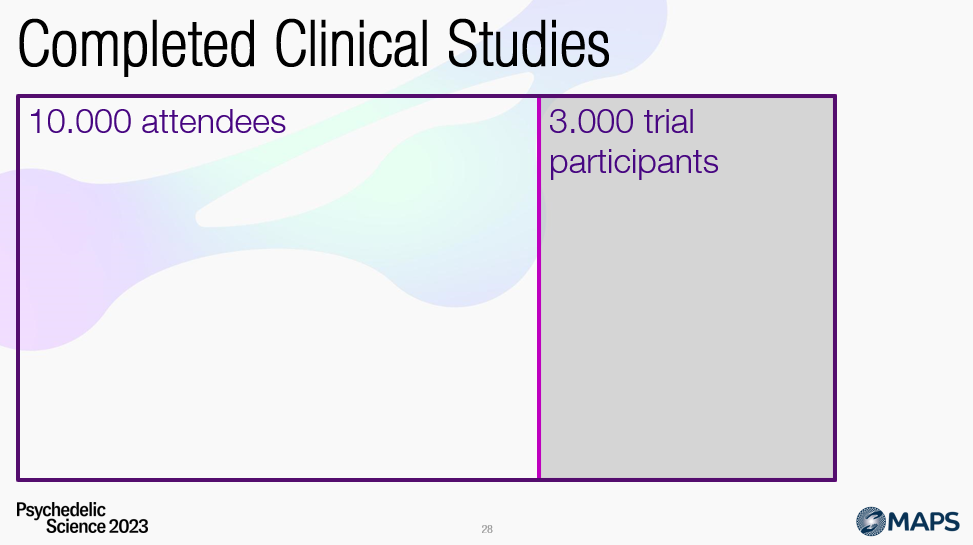

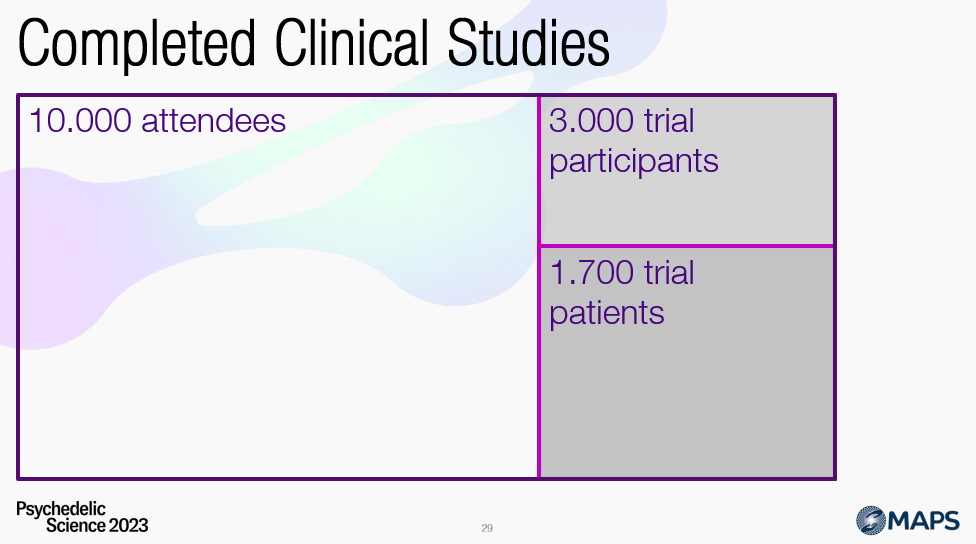

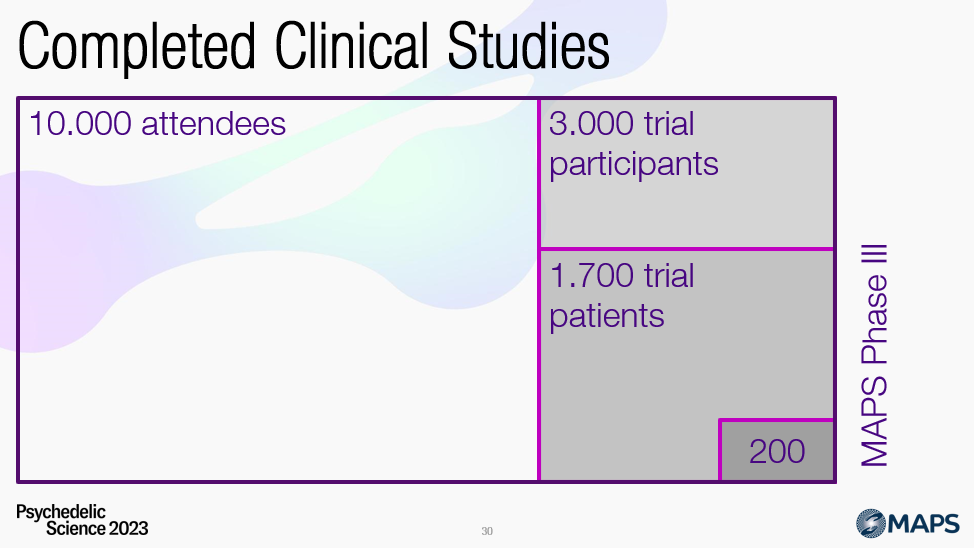

The total number of trial participants – including ongoing trials – sits at 3000 – about a third of the people at Psychedelic Science 2023.

And as you might remember from a few minutes ago, slightly more than half of these studies involved patients, versus also including healthy participants.

And this – 200 – is the number of participants in the MAPS Phase III study, fewer than are here in this room (for the live presentation).

I’m showing this right after the areas for which psychedelics are being researched, to show that there is a lot of potential, but that rigorous – as much as possible – studies are few in number.

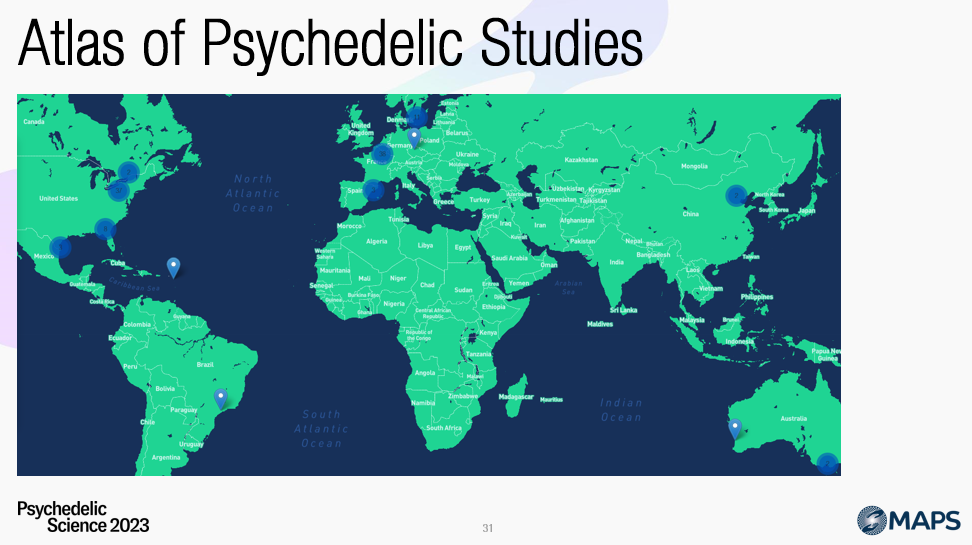

They are happening all around the world. In the ‘Atlas of Psychedelic Research’ I, Pedro Teixeira and colleagues, have mapped out the different places where clinical research takes place, covering most of the Western world and Oceania.

And progress is being made …

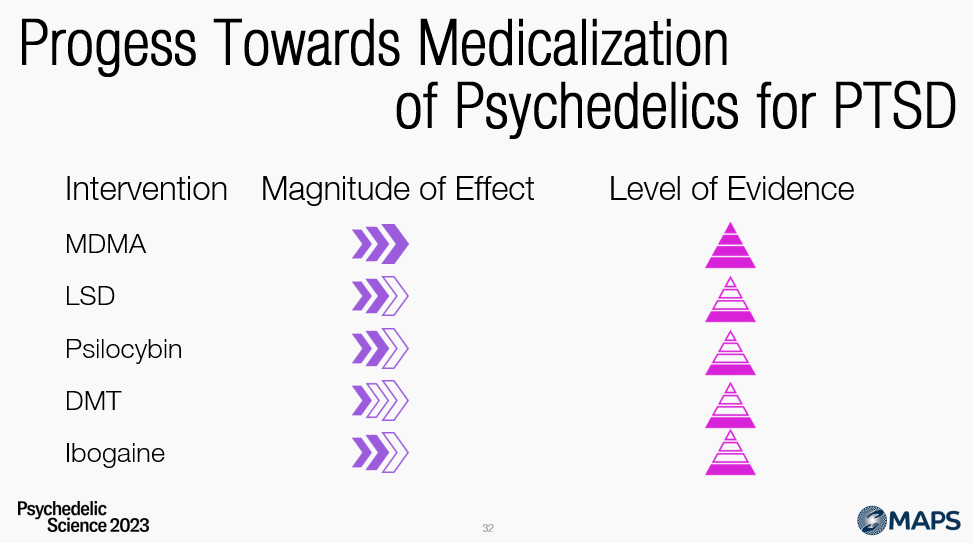

… as we can see on this simplified graph of psychedelics for PTSD.

Next to MDMA, there is research going on with LSD, psilocybin, DMT, and ibogaine. But research with these different drugs is in earlier stages, with lower levels of evidence and magnitude of effects currently observed.

So, what will we see in the coming years?

Will we see ‘Net Zero Trauma’ which Rick Doblin is striving towards, or will it be business as usual? Will there be a place for psychedelic-assisted therapy?

Though I have high hopes for PAT, I try and be mindful – to be the sober cheerleader – and not hold too tightly onto the belief that PAT is the next revolution for mental health care and personal development.

On the positive side, ‘we’re so back’, in 2019 there were two named psychedelic centres. Nowadays, there are over 20 research groups with psychedelic in the name, and thousands of researchers contributing to the understanding of their therapeutic application.

It’s no longer career suicide; psychedelics are a viable academic career path.

Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy (PAT) has shown considerable promise in early clinical trials. However, significant challenges must be addressed to ensure its transition from experimental research into mainstream therapeutic practice. Several roadblocks potentially stand in the way of wide-scale PAT adoption.

Firstly, there’s the issue of cost. PAT is expected to be significantly more expensive than conventional therapies, potentially up to ten times the cost of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) or traditional talk therapy. This raises questions about how it will be financed. Insurers are typically reluctant to cover high-cost treatments without substantial evidence of their superior effectiveness. Whether insurers will be willing to bear the brunt of these costs and under what conditions is a matter of ongoing debate.

Secondly, there’s the concern of who will provide the therapy. Will the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) be the only recognized training provider, and will regulatory bodies like the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or insurance companies accept their training protocol? Also, who else could offer suitable training? The availability of jobs for newly trained therapists and their integration into existing healthcare systems is another issue that warrants attention.

Thirdly, legal considerations pose a significant obstacle. While some jurisdictions have decriminalized certain psychedelics, this is a far cry from the comprehensive legal framework necessary for regulating these substances’ use in a therapeutic context. Achieving the required legislative changes to allow for the wide-scale use of psychedelics in therapy will undoubtedly be a lengthy and complex process.

The fourth roadblock involves safety concerns. While traditional therapy is not without its risks, including the potential for therapist abuse, these risks may be heightened in the context of PAT due to the intense psychological states it can induce. Although the health risks associated with psychedelics are generally low, particularly with classical psychedelics, non-classical psychedelics like ibogaine, MDMA, and ketamine carry certain risks. Establishing a robust regulatory framework to manage these risks will be vital.

The fifth challenge relates to manufacturing. It is critical to identify who will produce the psychedelics and at what cost they will be sold. It’s essential to establish production and distribution networks to ensure the safe and reliable supply of these substances for therapeutic use, without further inflating the costs.

Finally, there’s the issue of patents. Naturally occurring substances like psilocybin cannot be patented, but variations on these molecules, such as those developed by COMPASS Pathways, can be. This raises ethical and legal questions about access to these therapies. Will people be able to access these treatments outside of the specific company that patents the drug and therapy combination, or will a single corporation monopolize them?

Navigating these roadblocks will require a multi-faceted approach involving regulatory agencies, insurance companies, health professionals, legal experts, and manufacturers. It’s a complex path, but given the potential benefits of PAT, it’s a journey that is increasingly seen as worth taking.

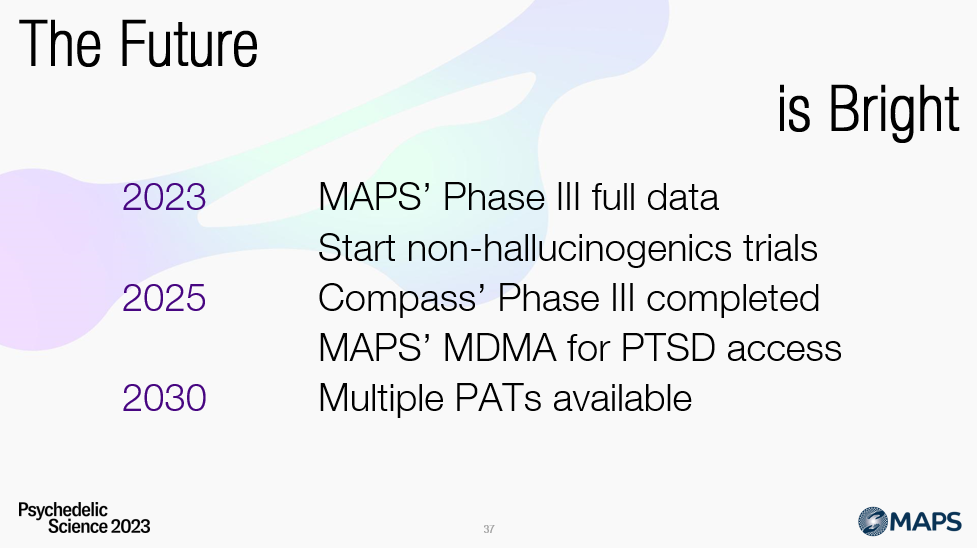

This year holds immense potential for psychedelic research, with several pivotal developments anticipated. One of the most awaited events is MAPS’ presentation of the full results from their Phase III(b) trial of MDMA-AT for PTSD. The submission of their application to the FDA is also expected within the next year, marking a crucial step in potentially securing approval for this innovative treatment.

Furthermore, groundbreaking research extends beyond hallucinogenic substances. The first-in-human trial of non-hallucinogenic psychedelics, also known as psychoplastogens, has begun. While it’s too early to predict the outcome, success in this area could substantially broaden the scope of ‘psychedelic’ treatments. This could open the door for millions more people to benefit from these therapies, including those suffering from cluster headaches, which have traditionally been challenging to treat.

Looking a bit further ahead, in about two years, we might witness real, practical access to MDMA-AT for PTSD patients. However, it’s worth noting that several roadblocks highlighted just before still need to be addressed before this vision can become a reality. As likely indicated by MAPS presenters, these challenges, ranging from cost considerations to training protocols for therapists, legislation, and safety, must be resolved to integrate this therapy into mainstream healthcare fully.

Additionally, COMPASS Pathways is expected to complete its Phase III study within two years. This milestone could pave the way for multiple psychedelic-assisted treatments to become available as we enter the 2030s. COMPASS Pathways’ research, which involves patentable variations of naturally occurring psychedelics, represents a significant advancement in the psychedelic therapy landscape. It underscores the potential for these treatments to become a central part of mental healthcare in the coming years, assuming that the trials’ outcomes are positive and the regulatory hurdles can be effectively navigated.

The coming years seem ripe with potential for transformative developments in psychedelic research and therapy. These breakthroughs, contingent on overcoming several challenges, could reshape how we understand and treat various mental health conditions.

Subscribe to The Bloom newsletter

A weekly email, sent on Tuesday (paid) or Thursday (free), packed with the latest

psychedelic research, news & actionable insights

Become a psychedelic insider

Get a Pro Membership to enjoy these benefits & support Blossom📈 full reports on Topics & Compounds

🧵 full summary reviews of research papers

🚀 full access to new articles

See Memberships