Earlier in November, the UC Berkeley Center for the Science of Psychedelics (BCSP) put up an excellent event discussing the cost-effectiveness of psychedelics.

I have summarized the key points from this event and highlighted some of the main questions about health economics and psychedelic therapies. Specifically, the discussion centred around whether it is economically feasible for MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD or psilocybin-assisted therapy for depression to be accessible at a large scale.

The speakers also examined whether group therapy models could make these treatments more cost-effective and widely available. Additionally, they explored if it may be possible to provide psychedelic-assisted therapy using a group model without compromising efficacy or patient safety.

The panel of experts included BCSP Director Professor Michael Silver, Dr. Elliot Marseille, Professor Jennifer Mitchell, and Executive Director Imran Khan. Their insightful discussion shed light on the emerging field of health economics as applied to psychedelic medicine.

Navigating the Trip: An Economist Charts the Course for Accessible Psychedelic Medicine

In his presentation, Dr. Elliot Marseille provided an overview of the economics of psychedelic therapies. He began by acknowledging the firm foundation of safety and efficacy data supporting these treatments while also recognizing there are still obstacles to wide-scale access and affordability.

Dr. Marseille went on to explain key economic concepts like the difference between “cost-saving” (where long-term reductions in medical spending offset upfront costs) and “cost-effectiveness” (good value for money, but not necessarily saving money). He emphasized that third-party payers will need evidence of value for money to provide coverage for psychedelic therapies. Preliminary data suggests MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD appears highly cost-effective, if not cost-saving.

Later in the talk, Dr. Marseille shared findings from his team’s (GIPSE) economic analysis on group therapy models. They found an approx. 20% reduction in variable costs compared to individual therapy protocols. More importantly, group therapy could substantially ease the shortage of qualified psychedelic therapists. Trading off some cost savings for increased accessibility will be essential to reaching more patients in need. Dr. Marseille concluded by underscoring the need for further research and economic evaluations across different psychedelics and indications.

Question & Answer: Exploring Emerging Pathways and Pitfalls for Psychedelic Medicine

The Q&A opened up with an inquiry about the significantly higher estimated costs of MDMA used in therapy protocols versus the street costs of ecstasy/Molly. Dr. Marseille explained factors like the expenses of clinical trials and commercialization and MAPS‘ partial reliance on private investors expecting returns. There was also mention of potential competition helping lower future MDMA pricing.

A later question also discussed the differences between natural versus synthetic psilocybin and associated regulatory requirements. Prof. Mitchell noted analyses finding natural psilocybin could become more costly when factoring in evaluations ensuring quality/purity standards.

The following exchanges centred around optimizing protocols and models for different cohorts and conditions. Regarding questions around group therapy suitability across PTSD subpopulations, Prof. Mitchell highlighted careful precautions taken with factors like military sexual trauma. She stressed comparisons and more data regarding individual versus group format efficacy would be needed. In terms of flexibility in real-world psychedelic-assisted therapy models, Dr. Marseille discussed possibilities like titrating numbers of psychedelic sessions based on patient responses.

The next question concerned non-hallucinogenic psychedelic analogues in development and their potential advantages. Prof. Mitchell suggested their regulatory pathway may resemble something like SSRIs more closely. Dr. Marseille also weighed in on open questions about the specific therapeutic mechanisms of psychedelics, allowing for different compounds with and without strong psychoactive effects.

The latter part of the Q&A discussion delved into issues around expanding access and mitigating risks. Questions arose around insurance coverage and distrust from marginalized communities. Prof. Mitchell emphasized the value of care teams reflecting patient diversity. Dr. Marseille highlighted the potential for small pilots to uncover effective outreach models. Regarding safeguards, Dr. Marseille conveyed concerns over the growing availability of extremely potent psychedelics without proper containers for navigation.

Exchanges also touched on lingering unknowns with psychedelic therapies. Attendees asked about requirements for animal testing and post-approval monitoring. Prof. Mitchell confirmed Phase I safety assessments involve animal studies, while specifics on follow-up data collection are still developing. In a similar vein, Dr. Marseille discussed ideas for modelling broader wellness impacts from naturalistic psychedelic use. He is involved in reviews examining related physiological and psychological evidence.

The finale of the discussion centred on thoughtful reflections about avoiding commodification and managing expectations. Dr. Marseille emphasized wanting psychedelic access accompanied by necessary safeguards and warning of self-aggrandizement risks. Likewise, Prof. Mitchell expressed concerns over across-the-board decriminalization, absent proper understanding of psychedelics’ sensitivity to environmental factors. Both speakers closed by stressing the importance of supporting those potentially destabilized by this treatment paradigm shift.

Full Transcript of ‘Health Economics & Psychedelics, with Elliot Marseille & Jennifer Mitchell’

This transcript has been edited for clarity. Mistakes are my own, please refer to the video if anything is unclear. Comments are added between brackets [like this].

Elliot Marseille

I’m eager to share some of the developments in the economics of psychedelic therapies. But more than that, I’m eager to share ideas with all of you. I’m looking forward to the discussion we will have after this.

I want to acknowledge the co-authors on the paper that’s coming out shortly in Frontiers of Psychiatry, on the economics of group psychedelic therapy. And you can see the names of the co-authors on the slide. And I also want to extend my thanks to the BCSP team. Imran Michael, Rebecca, Christina, I know other people are working behind the scenes.

So, I want to start with a general statement about where I think the field is. Now, one of the clear things is that we’re standing on a solid foundation of demonstrated safety and efficacy. And there are few papers on this subject. In fact, there are quite a few, and they’re coming in fast and furious. Probably, some papers are being published right now as I speak.

It doesn’t end here. So what can you say about this? Wow, is one thing you can say. That’s a lot of encouraging efficacy and safety data. But I got to earn my keep here. I’m an economist, which means I am a proponent of the dismal science. Many people believe that we’re entering a new era of mental health treatment. Even though I’m an economist, I am also one of those people. But there are obstacles, there are problems that are worth pointing out. And this is the this is the downer part of it. There’s only one psychedelic therapy that has gotten to Phase III. And that’s MDMA for PTSD. Many hearts have been broken, following encouraging results from Phase I and Phase II trials that didn’t pan out in Phase III.

A lot of the published studies have major methodological limitations, small sample sizes, poorly controlled, open labels, and short follow-up times. Probably some other problems too, but I’ll stop there. Some of the results are not don’t show unequivocal superiority to the standard of care. Remember, the standard of care is not ineffective. SSRIs really do help some people. And then finally, the last one is sort of closest to my heart as an economist, which is to say that just because something has superior efficacy, doesn’t mean that it’s good value for the money, two different things. And while we’re piling on problems, I can add one more, which is the inevitable decay of measured benefits as you move from well, resource-controlled clinical trial environments to real-world effectiveness.

[The highly controlled experimental environment of clinical trials is carefully configured to optimize conditions for demonstrating an intervention’s efficacy. However, effectiveness in real-world practice tends to be dampened to varying degrees once supports are removed and “noise” is introduced. Key factors include differences in patient adherence, provider administration skill, sample biases, concurrent treatments, and assessment procedures. For example, trial participants are often more motivated and have fewer comorbidities than patient populations, while real-world providers have a wider range of capabilities in intervention delivery. Though some decay is inevitable as treatments translate into usual care, the goal is to retain as much benefit as possible.]

Still, we should celebrate what’s been achieved to date. So what’s next? I would say one of the things that among the things that are next is guaranteeing access to all who can benefit, demonstrating value for money and supporting the financial viability of the nascent psychedelic therapeutic enterprise. None of this will happen unless third-party payers are convinced to make this a benefit for their members. If that doesn’t happen, this is really great for people who can afford to pay out of pocket, and it will make no difference on a public health scale. So I want to back up and give you a quick primer on a critical concept in my field which will hold us in good stead as we move forward. People conflate the idea of cost-effectiveness with cost-saving. These are two distinct concepts. And I want to untangle them.

So the question is, what’s the difference between something being cost-saving and being cost-effective? If something is cost-saving, what it means is that the initial cost is more than compensated by reductions in medical care costs over time, because people are better, right? So that’s terrific. When that happens, it’s a dominant option in the turn of art of my business, it’s dominant provides benefits and saves money.

If something’s cost-effective, that’s a much lower bar, it just means that it’s good value for the money. So if it’s cost-saving, it’s cost-effective. But not everything that’s cost-effective is cost-saving. And let me just say, as an aside that most interventions aren’t cost-saving. Most medical, clinical and public health interventions are cost-effective, but again, not cost-saving, and a bunch of them aren’t even cost-effective. But that’s a conversation for another time.

A little bit about the service delivery context. Let me summarise it this way, the demand for conventional behavioural and mental health interventions greatly exceeds the supply. There are long waiting lists now for standard mental health treatments. And with the advent of psychedelic therapies, that could get worse. On the supply side, there are various constraints on the training of new therapists, first of all, the training capacity, the perceived risk of getting trained, and then maybe not getting the necessary approval to practice time constraints. It’s exhausting, I am told, and I could understand that to do an eight-hour psychedelic session with somebody, so even people who are trained, are not necessarily going to be doing this full-time.

Also, psychedelic therapy is catnip to a certain kind of politician. So earlier this year, a legislator in the Massachusetts legislation, tried to cap the reimbursement for MDMA therapy at $5,000 per patient. I don’t think it went anywhere, but it’s kind of a warning shot of a kind of interference that will also constrain supply.

So what can you say about all of this? One of the things you could say is “there’s no such thing as a free lunch”. And this dictum is about as close to the DNA of a health economist as anything can be. It’s all trade-offs, it’s trade-offs all the way down. And the job of the policy analyst, the job of the health economist, is to optimise among less than perfect trade-offs. But it could be that group therapy.

Group psychedelic therapy is an exception to this. So it could be that a move away from individual highly clinician-intensive psychedelic therapy, to group settings could ease the supply of effective clinicians reduce costs, and possibly enhance benefits, we can return to that question because it’s an important one. So it could increase access to all who can benefit while also saving money. And if that’s true, it’s kind of a big deal.

So now let’s just address a really basic question. Are psychedelic therapies cost-effective? MDMA for PTSD? Yes. So two analyses, using both Phase II and then later Phase III data suggest not only cost-effective but cost-saving from the point of view of the healthcare payer. And if you included broader societal benefits, mind boggling bargain the cost-effective or cost-saving. So let’s look at psilocybin and major depression. It looks like it’s cost-effective. A member of our team Anton Avanceña is about to publish a paper on psilocybin in therapy for major depressive disorder as a third-line therapy. So it looks to be cost-effective, but not cost-saving.

Marseille, E., Kahn, J. G., Yazar-Klosinski, B., & Doblin, R. (2020). The cost-effectiveness of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for the treatment of chronic, treatment-resistant PTSD. PLoS One, 15(10), e0239997.

Avanceña, A. L., Kahn, J. G., & Marseille, E. (2022). The costs and health benefits of expanded access to MDMA-assisted therapy for chronic and severe PTSD in the USA: a modeling study. Clinical Drug Investigation, 42(3), 243-252.

So now let’s get a little bit into the weeds on the economics of group psychedelic therapy. So we use data from two trips to trial sites to address these questions. How much money could be saved, by moving to group therapy? How many clinician years of time to be saved? And what does this imply for access to care? Let me just say, by way of background, I’ve been hearing conversations for years about the need to move away from the two therapist one patient model for a long time now, I think it was adopted for very good reasons to signal concern about safety. No argument with with the original decision to go with that. It more expensive mode of therapy. But there’s been a lot of conversation; we need to move away from that, and it will save a lot of money. So our team said, Well, okay, how much money let’s crunch the numbers and see what we can learn here.

So, we got empirical data on the cost of delivering group therapy from two sites, the Oregon Health and Science University, Christopher Stauffer’s group that was doing an MDMA trial for veterans in a group setting, and Sunstone Therapies, psilocybin trial using group monitoring of patients with cancer who had major depression. So let’s look at the group PTSD protocol. One is that of the 14 sessions, that is the preparatory sessions to act psychedelic sessions, and then the follow-up sessions of those 14 sessions. 11 had six patients. So that’s the group including one of the two, eight-hour sessions. And the other defining characteristic is that for their for clinicians in the group setting, and also in that follow-up setting.

So you can see that the savings in cost might be a little less than you would think because, in the longest group setting, you’re doubling the number of clinicians, and the clinician-to-patient ratio was not as great as it was in the individual therapy protocol. But it’s not. Right. So we’ll see how that plays out here. For psilocybin, the Sunstone protocol, the defining feature is that it has five sessions, one active psilocybin session. And in four of those five, the monitoring is done by a senior clinician who has a closed-circuit TV, and is watching what’s going on, in all four of those rooms. So, instead of having that person be in each room, he or she is monitoring four rooms at a time [as clarified during Q&A there is always someone with the patients, just not the senior clinician]. So that’s where you get the savings. You could say it’s not really group therapy, I’m not going to argue the point it’s group monitoring, but the effect is the same. It’s just a stretch, it’s to extend the clinician pool.

So here are the results. If you compare the two, relatively modest reduction in total variable costs of about 20%, but significant reductions in clinician costs of about 51% for MDMA, PTSD, and 35% for psilocybin, for major depression. The cost of the MDMA-assisted therapy is highly sensitive to the cost of the MDMA itself. Let me stress that I don’t know what the cost of MDMA is going to be. And, you know, MAPS is working on various price levels, but I have my ear to the ground. So I have some reasonable range. I never present a specific number, because I don’t know what it is, but I do present ranges.

The key point here is that the MDMA therapy itself is 54% of the total. And what you can’t see there is that the total cost of the therapy is about $17,000. And then for group therapy, it’s the total cost is about $13,000 and the cost of the MDMA that MDMA itself constitutes about two-thirds of the poll. Now the MDMA cost doesn’t change as you go from individual to group, the cost of the MDMA is across the MDMA about $9,000 In this particular estimate, but because you have fewer clinician costs, the proportion that’s devoted to MDMA is higher in the group therapy setting.

Psilocybin-assisted therapy, in the individual protocols, and session setting, the total cost of the therapy is about $4,700. The psilocybin itself is about 32% of the total or $1,500. Group monitoring is about $3,900 for the total per-patient cost. And the proportion of the cost that is devoted to the psychedelic material itself goes up to 39%. So I was interested in understanding what would happen if you varied the number of people in the group. So this graph shows the percent reduction in total variable cost, as you increase on the horizontal axis, the number of patients in the group sessions. So the base case here is six [patients], that’s what Christopher’s group used in Oregon.

You can see that as you move to the right hand side of the graph, that the incremental gains in savings kind of levels off, you know, it’s not a straight line, it levels off. It could be that six is a good, a good number. If you increase it, you get diminishing returns and at a certain point, safety considerations come to the fore. Okay, so now let’s talk about payers, because it’s such a critical issue. And obviously, they care about cost. And they care about cost-effectiveness. I am told that payers care a lot about the time to break even.

And so we looked at that, and I’ll share something about it. I’m slightly sceptical. Remember, breakeven means anything after that is you’re saving money. But most interventions don’t save money. But it’s still a useful metric. Another thing that they definitely look at is the cost per member per month [PMPM]. If they’re bringing a new intervention online, they need to know how much that implies they need to raise their premiums.

It turns out that the cost of MDMA actually has a very modest effect on the break-even time for MDMA-assisted therapy. As the cost goes from $1 per milligramme, that 20-fold increase to $20 per milligramme. The break-even time only increases from 3.7 years to 4.7 years, I thought that was a little counterintuitive, but that’s the way it is. And so then this other issue of the increment to the payers budget, affordability PMPM, those issues.

Here’s a rule of thumb: if a new drug increases costs by $100 million, for a large private payer, like Kaiser, that could be a red flag. And so we looked at Kaiser, there’s a lot of numbers here, you know, we looked at the total revenues, and how many members would be eligible for MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD. And here’s what we get if the MDMA is $5, per milligram, the cost would be $439 million spread out over five years. So that would be potentially a red flag, and certainly at $20 per milligram at $630 million, would be a red flag that could give them pause. So it seems to me that insurers, payers of all kinds, both public and private, are going to be concerned about the total cost of delivering the therapy.

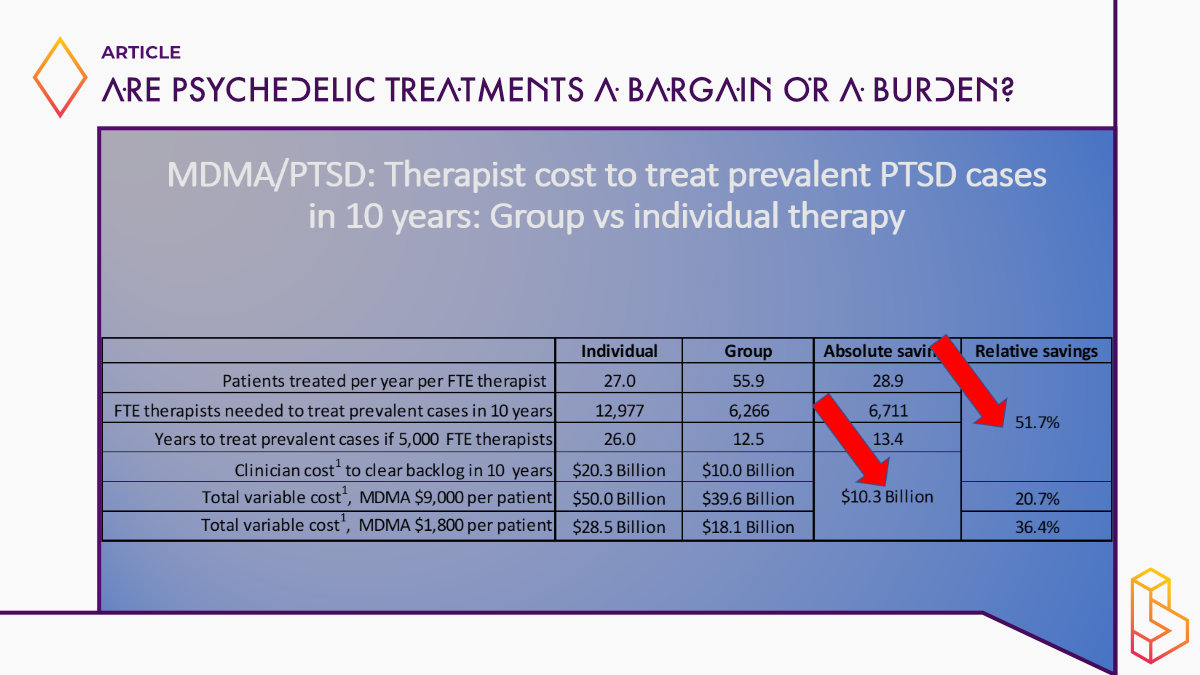

A little bit on the macro effects of MDMA-assisted therapy if it became available at scale. What does this mean? What would the impacts be? So there are a lot of numbers here, but I just want to draw your attention to a couple of couple of points here. The first row patients are treated per year per full-time equivalent therapist. If you use the individual model, they can treat 27, with the group model about 56. Look at the third row; it’s the years to treat all prevalent cases of eligible people with PTSD in the United States. If you had 5000 additional full-time equivalent therapists, it’s 26 years for the individual model and 12.5 for group therapy/monitoring these are big differences, namely 53%.

It’s like expanding the available pool of trained clinicians by 50% or doubling it. And the cost implications are not insignificant either. So I gotta say, this was a little bit of a surprise to me when we started this analysis, I thought we were going to show big reductions in cost because we have group therapy, so the per person who completes it’s got to be much lower. But for reasons that I touched on, it’s not entirely group [therapy/monitoring] and you have to double up clinicians for some of these large group sessions, the savings, the overall savings aren’t that much. But the savings and clinician time is quite significant. And given that everybody who’s looked at this sees the limited number of trained clinicians has been a major bottleneck to access, I think these findings are, are important. So here’s another way to look at it.

The number of full-time equivalent clinicians on the horizontal axis, and the years it would take for half of the eligible prevalent population with PTSD in the United States to receive treatment. And if it were 2000, clinicians, it would take 35 years longer to do it with individual therapy than with group. And even at 12,000, there’s still a three-year difference.

Broader societal benefits, such as increased productivity, a really important paper by Davis et at. all came out last year on the economic burden of PTSD. The non-medical costs for people in the military, both active duty and veterans. So we’re looking at productivity losses, unemployment, and a couple of other factors, which works out to about $9,400 per person per year. So we put this in our model.

And here are the cost-effectiveness results. So three prices, three costs of the MDMA protocol, assuming three sessions, and then we’ve got the direct medical costs on the left divided by individual and group and full net Medical Care Plus productivity consequences on the right. It’s cost-saving for every one of these configurations, except at $13,500. For the individual therapy, looking only at cost savings to healthcare payers were at $2,300 per QALY, and the higher price of a therapy. It’s at $100 per QALY. And for group therapy, it’s $3,800 per QALY. What does this mean? You’re asking me? Is that good or bad? Like how many what how many dollars per quality is good. So in the United States, roughly speaking, between $100,000 and $150,000 per QALY is considered okay. So this is highly, highly cost-effective or cost-saving, however you want to slice it.

[A QALY stands for “quality-adjusted life year.” It is a measure used widely in health economics and outcomes research to quantify the value provided by medical interventions. Specifically, a QALY score factors in both the quantitative extension of life expectancy as well as the quality of remaining life years, as adjusted to account for reduced quality of life associated with disabilities/disease. One year of perfect health is worth 1 QALY. In cost-effectiveness analyses, the cost per QALY gives a standardized dollar value for how much money is spent for each year of perfect quality life that an intervention provides. In the US, treatments costing less than $100,000-150,000 per QALY are typically considered a good value.]

So, MDMA-assisted therapy is likely highly cost-effective, if not cost-saving, for both the general population and for military personnel. Group therapy can help solve two critical problems guaranteeing access, lowering overall cost, and, most importantly, easing the shortage of qualified clinicians. Broader societal benefits are likely to exceed the health care costs, and the savings in broader societal costs are likely to exceed the savings in health care costs alone.

What’s the broader agenda for the economic evaluation of psychedelic therapies? Our group, the Global Initiative for Psychedelic Science Economics (GIPSE). We’re about to publish a paper, the first author is Anton Avanceña, on the cost-effectiveness of psilocybin for major depressive disorder. We’re also working on psilocybin for smoking cessation with Matthew Johnson.

That’s big-time public health because of smoking [impact on the economy & health] and we’re working on an economic model of ibogaine for opioid use disorder. We’re also in conversation with the Psychedelic Health Equity Initiative (PHEI). This is not funded yet, but we are hoping to work with them. It’s looking promising to work with them on four pilot sites that are pioneering how to bring underrepresented communities into the fold, about how psychedelic therapies become available to them. So they’re innovating on ways to reach out to typically underserved populations.

The thing I really want to bring forward is our plan to make all of this work publicly available, free of charge as a public good to any researcher who can make use of it. We want to have state-of-the-art, the best clinical information on the course of depression, the course of opioid use disorder; we’re also working on alcohol use disorder. So we want those to be out there and be the reference models for these disorders and these interventions to address them.

But there’s another way to think about what the broad agenda for economic evaluation is. If you take the number of molecules that are under consideration, there are N combinations of molecules that people are talking about, right? And you multiply that by the number of psychiatric indications that these could be relevant for. And you multiply that by different kinds of patients subpopulations severity of the different disorders. And you multiply that by the variations in treatment protocols that are available. You multiply that by the number of countries; you get a number; I did the calculation. Here’s the number.

Q&A

Imran Khan

My name is Imran Khan. I’m the Executive Director of the Berkeley Centre for the Science of Psychedelics. And it’s my pleasure to moderate this post-lecture panel. I’m going to kick it off with a couple of questions. And then we’re going to have a Q&A. So if anything you’ve heard today sparks a question you want to ask Elliot Marseille or Jennifer Mitchell, please do raise your hand in a minute.

I also just want to reintroduce Jennifer Mitchell to the panel, amongst many other things. She is a Professor of Neurology at UCSF, and I think her work is part of the reason we’re all here discussing this. It’s an absolute pleasure and privilege to have her here. Jennifer, I wonder if I could bring you in at the beginning just to kind of zoom us out for anyone who’s been kind of living either under a rock or on Mars or somewhere else where the words MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD mean nothing. Could you talk us through why are we here talking about this? And why is this such an important issue right now?

Jennifer Mitchell

I think it’s an important issue right now because the second of two Phase III trials have just been completed that have evaluated the effectiveness of MDMA-assisted therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder. The first was in a population with severe PTSD. And the second was in a population with moderate to severe PTSD. And that was funded by a sponsor called MAPS PBC.

MDMA-assisted therapy for moderate to severe PTSD: a randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial

Mitchell, J. M., Ot’alora G, M., van der Kolk, B., Shannon, S., Bogenschutz, M., Gelfand, Y., … & MAPP2 Study Collaborator Group. (2023). MDMA-assisted therapy for moderate to severe PTSD: a randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Nature Medicine, 1-8.

Imran Khan

When we talk about moderate to severe PTSD, what are we talking about? What’s that condition like the people, and in terms of the results of your paper, what what did you find?

Jennifer Mitchell

We found that those who received MDMA in association with therapy had a larger decrease in PTSD symptomology and also a better improvement in functional impairment compared to those who received placebo plus therapy. And then in terms of what PTSD actually looks like, obviously, it can be quite debilitating. It depends on how severe it is, but a lot of the individuals that we treat that we see with severe PTSD have trouble leaving their houses, they have trouble interacting with their environments, and they don’t want to drive. They don’t want to come into the treatment centre. They don’t want to interact with strangers or even with friends and family.

In terms of the current treatments available for PTSD. We have two FDA-approved SSRIs; sertraline and paroxetine, that people use to treat PTSD. But as most of you know, SSRIs were not developed to treat PTSD, they were developed to address issues around depression. And there is a huge comorbidity between PTSD and depression. And so it seems as though these drugs can be partially effective in some people with PTSD, but are typically not fully effective. Additionally, we have cognitive behaviour therapy, we have something called prolonged exposure therapy, which, as the name implies, means you’re exposed to your trauma over and over again until, hopefully, it doesn’t have quite the hold on you that initially had, as you could imagine, most people drop out of that form of therapy. And then we also have CPT. So those are the two behavioural therapies that that are currently used for treatment.

Imran Khan

You just published the second part of the Phase III trials. I thought one of the interesting things in that paper was that you changed the demographic slightly of the study population. We’re here talking about health economics and who these substances will potentially benefit. One obvious question that arises is, who will benefit? And will it be the population as a whole? Or will it be certain subsets?

Jennifer Mitchell

Correct. So I think that both individuals on the care teams at the study sites, and the study sponsor [MAPS PBC] pretty quickly recognised in the first Phase III trial, that we weren’t actually reaching the full population that we were hoping to reach. And I think part of that was because when you sit down with somebody at the end of the subject screening period, and you say, okay, you know, how do you feel about changing your schedule to accommodate 19 study visits? A lot of people from places of privilege say, absolutely, I’ll do that, of course, this is very important. And people from more marginalised places, say things like, I’m working two jobs, and I’ve got kids, and I’m taking care of my parents, and I don’t have a car. Could you help me? And during that first study, we had to, unfortunately, say no. We did not have the funding available to help you with that problem. And then after sort of talking with the sponsor, God bless them, they came up with the funds, so that in the second Phase III trial when that happened, we could say, absolutely, we can provide childcare money, reimbursement for lost wages, we can provide transportation to and from the treatment centre. And that made a huge difference.

Imran Khan

So, Elliot, we’re hearing from Jennifer’s study that this is effective, that it works, that it helps successfully treat PTSD in a way that really can’t compare with existing treatments. We’re also hearing that it works for diverse populations, we’re hearing from your work that it’s cost-effective and potentially cost-saving, too. When you say all this to payers and other stakeholders, what kind of response are you getting from the economic argument?

Elliot Marseille

Full disclosure: I’m not in conversation with many payers. I want to be in a more direct conversation with them. It’s more secondhand. I’m hearing what other people say payers are thinking about. I think there’s a lot of wait and see, a lot depends on the specific regulations that accompany the FDA approval, which patient subpopulations it’ll be approved for, whether the full therapy will be if we’re thinking about reimbursing the full therapy or just the MDMA itself. So there’s there’s a lot of uncertainty there.

On the other hand, it seems to me that at a certain point, this becomes irresistible. The efficacy is so great, and the safety profile is so good. And I also think, at a certain point, political pressure begins to matter to payers, that just the demand for this will become palpable. People are going to other countries for retreats to get these kinds of therapies now, particularly veterans, and that’s one of the things that’s working in our favour. It’s been remarked on many times, and I will remark on it one more time. Everybody cares about veterans. It’s not a partisan issue. So the possibility of getting bipartisan support for MDMA for PTSD looks pretty promising. I’m optimistic that payers will come around.

Imran Khan

And Jennifer, Elliott talks about the potential value of a group model in his lecture. Obviously, that differs from what’s been studied so far. And I guess we’re at this interesting juncture where in terms of formal academic studies, this particular model has been studied. But that won’t necessarily be what it looks like in the real world in the future. How do you know, based on what you’ve seen in your studies, how will that go? And should we be looking at group models more? And what do you speculate about the naturalistic use as well?

Jennifer Mitchell

My guess is that the value of a group model is really going to depend on the cohort that you’re looking at. For example, veterans really do enjoy being in a cohort of veterans for all sorts of things. But you could imagine that there are some indications in which a group cohort would be less appropriate. I think that’s one consideration, I think another thing to consider is that we don’t yet have great efficacy data from some of these group settings. And that’s really key. So the cost-savings, and the cost-effectiveness will definitely be influenced by the efficacy. If it turns out that group therapy, for whatever reason, isn’t as effective as individual therapy, then that changes the whole dynamic.

Elliot Marseille

In a perfect world, we’d have head-to-head trials of group versus individual therapy. It’s expensive, that’s probably not going to happen. But we do have some early positive signals, like some Sunstone Therapies work on psilocybin, which I mentioned here. They got roughly comparable, maybe somewhat better efficacy in the group setting that has been reported as an individual. So it’s not enough one trial, but I think there’s reason to be hopeful. And to underline something Jennifer said, it’s not for everybody. Group therapy should be an option, not mandatory. There are some people who, it’s not for them for any number of reasons. And so, again, it should be available to people, but individual therapy protocols should also be available. They’re also very cost-effective.

Imran Khan

Elliot, I know that in your previous work, you spent lots of time looking at HIV AIDS, and the health economics of how do we improve access to treatments. What are the lessons that we, as the psychedelic community, can learn from the successes of that work?

Elliot Marseille

A big part of it is the removal of stigma, allowing people who are otherwise, ashamed of having HIV to come forward without risk of being ostracised, or even worse in some areas. So I think we’re moving in that direction with mental health in this country. People are much more willing to disclose that they have a mental health problem. So I think that’s an extremely important part of it, and it extends and is necessary for the kind of activism that we’re going to need to lobby for these therapies. The other thing that was sort of revolutionised, the approach to HIV AIDS was the advent of therapy that really worked. So you can’t argue with that, right? And I think we’re, we’re certainly looking at that with MDMA for PTSD. And I have a feeling that we will see very dramatic efficacy for interventions with other behavioural disorders like addictions and alcohol use disorder, what I’m seeing coming from Matthew Johnson on tobacco. So I think it’s going to be really compelling.

Question

I was surprised that the costs you were talking about for the actual MDMA for the therapies are two orders of magnitude above the street value of XTC. I thought it would be higher, but I didn’t expect it would be that much higher. I mean, people today are making profits on it? So I was wondering how that works. Why is it so expensive?

Elliot Marseille

There are people from MAPS here who may want to provide more information on this. Let me just say this. I think the cost of getting through the clinical trials and FDA approval and commercialization was much more costly than anybody expected. And so if MAPS is going to make good on its pledge to return a portion of revenues to the 501c3 [non-profit] to continue to support the public good aspect of their work.

The other thing is they’ve been in a position where they’ve had to bring in private investors who want to see some kind of return. So there are a lot of factors there. I know it’s surprising. Again, the numbers I gave are not the numbers, the numbers don’t exist, but it’s my best sense of where we’re going to end up.

Question

My question is about the access issues you started to talk about regarding payers and trends. I’d love both of your thoughts on the burden of PTSD – especially among marginalized groups around race, age, and gender – and then connecting that to what payers and insurances normally cover them. What are the trends? Will coverage and access intersect for these groups? Or will this therapy remain relatively boutique and out-of-pocket?

Also, given the distrust of healthcare, how do you convince marginalized groups that psychedelic-assisted therapy is a viable and accessible option? As a person of color where mental health is highly stigmatized, this would seem ridiculous to my parents or older generations in my community. So thoughts on both the payer side and community trust/access issues? How to convince people this could be an option for underrepresented communities?

Jennifer Mitchell

I think that’s the $20 million question – how do we obtain access for those communities? Over the trial course, and in general, it’s been very difficult reaching the PTSD patients most in need. They don’t typically present in Western medical settings seeking help. I don’t have an easy solution. What I can share from the clinical trial view is that, as researcher Katrina Green says, people like looking in a mirror. Diverse care teams educated in diversity and inclusion perform much better in engaging communities. I believe we saw that play out through the MDMA PTSD Phase III trials.

Elliot Marseille

I strongly advocate piloting different approaches to see what works. That’s why I’m excited about the Psychedelic Health Equity Initiative. They’re funding community groups already working with marginalized groups to introduce psychedelic therapy. Let’s use trial-and-error to determine what’s effective.

Imran Khan

I’ll add that our Berkeley Psychedelic Survey this summer – a nationally representative poll of US voters on psychedelics – found overall support for access and research, especially for terminal or veteran populations. But we saw clear demographic skews in familiarity and openness to psychedelics – more common among white, educated, higher income brackets. I think ethnic minority groups may have knee-jerk stigma seeing MDMA as a dangerous, unacceptable treatment. Alongside economic studies, more public engagement around the research and breaking down harmful stereotypes is needed.

Question

If MDMA is approved, will therapist requirements be specified? Could group protocol evidence still be rejected due to risk regulations? Also, regarding HIV treatment cost reduction via generics – a single supplier won’t optimize cost-savings long-term. Competition is key for systemic benefit, though I understand MAPS’ need to recoup investments.

Jennifer Mitchell

I’m not an expert on REMS plans between sponsors and the FDA. However, the FDA doesn’t usually regulate therapy specifics. It would be surprising if they imposed rigid therapeutic restrictions. I could see basic guardrails like buprenorphine’s prescriber limits, and extra oversight/training requirements to ensure MDMA providers are properly qualified. But heavy-handed therapy conditions seem unlikely from the FDA.

Imran Khan

Elliot, would you be able to tell us a story of the generics in HIV AIDS and how that changed things?

Elliot Marseille

Originally Big Pharma adamantly opposed two-tiered HIV drug pricing – one for rich countries, putting meds out of reach for developing nations. After sustained activism essentially shamed them, they gradually adopted tiered pricing. They warned cheaper generics for poor countries would spur dangerous black markets in wealthy regions. But that never really materialized, at least not at scale. It took persistent heated campaigning for them to concede. You can see HIV drug prices slowly dropping over the years since.

I don’t expect that here. MAPS effectively holds a monopoly – not technically a patent, but temporarily behaving like one for maybe 6 years post-approval. Afterwards, generics can produce, likely prompting rapid price decreases. There’s another potential MDMA price control as well – competition. Why MDMA for PTSD versus psilocybin or LSD? The reasoning is unclear presently. If other potent, more affordable therapies arose targeting PTSD, that too could compel price drops.

Question

You’re saying that the FDA then won’t have quite such a strict protocol for what this will look like. Does that include the video monitoring of the sessions, things like that that won’t be required? Or do you have any idea about that?

Jennifer Mitchell

In general, the FDA doesn’t require video monitoring for anything that’s not within their purview. And that is a part of Phase III for a variety of reasons. But I don’t see the FDA continuing that moving forward post-approval.

Question

In terms of the group therapy models that you’re describing Elliot, did it mean that there wasn’t a therapist in the room with those folks, or was there someone monitoring, and someone in the rooms?

Elliot Marseille

There’s always a therapist in the room with the patient. That’s right. The difference in the traditional model, there are usually two all the time. So the ratio is more attenuated. Nobody’s left alone.

Question

You mentioned earlier that there are some diagnoses which might not benefit from psychedelic group therapy so much. Could you elaborate more on which diagnoses those might be and why that might be the case?

Jennifer Mitchell

I was referring specifically to considerations around different PTSD subgroups and group therapy suitability. For example, at the VA when discussing group therapy, we’re very careful distinguishing between military sexual trauma (MST) with female participants versus combat-related trauma groups with male participants. Those can never be mixed. With that in mind, I think some groupings may work better than others.

Question

Jennifer, I wanted to clarify – did you say MDMA was given in conjunction with additional therapies? And if so, what modalities?

Jennifer Mitchell

Both study arms received psychotherapy along with either MDMA or placebo. The psychotherapy approach was developed by MAPS over many years – their manual is available on their website. It’s patient-directed, unlike manualized PTSD treatments like prolonged exposure.

Imran Khan

Has any exploration begun around combining MDMA with other therapeutic modalities like mindfulness or yoga? And regarding efficacy data, have those conversations started?

Jennifer Mitchell

If interested, search clinicaltrials.gov for “MDMA therapy” to find several studies underway, some sponsored by MAPS and others VA-backed. The VA group is very curious if MDMA could boost efficacy when combined with their usual psychotherapy. Those trials haven’t started yet but there has been much discussion.

Question

Regarding session cost estimates – for both MDMA and psilocybin – how were those derived in terms of number of administration sessions plus follow-ups? Once approved, will private clinics have flexibility offering varying psychedelic session schedules (i.e. one session with two integrations or two sessions with additional follow-ups), perhaps as a cost-savings mechanism under insurance plans? Do you envision that level of real-world protocol flexibility?

Elliot Marseille

There’s huge variability currently. The MAPS PTSD protocol involves up to three MDMA-assisted sessions and three integration sessions each – so nine integration sessions total. The psilocybin cancer distress protocol is a much lighter touch – just one psilocybin administration and two integrations. So the optimal session frequency is unclear – are there diminishing returns? One clinician suggested titrating based on patient response. Like one session, assess response, then consider another session as needed up to three or four total. It’s unmapped territory with room for current standardized protocol innovation.

Jennifer Mitchell

For MDMA-PTSD, I hope early real-world adoption sticks closely to Phase III methods – FDA post-marketing surveillance depends on that consistency to effectively monitor outcomes, side effects, and subgroups benefiting more or less. Deviations will complicate data collection. We want to understand the impacts once MDMA reaches broad off-trial usage – who does it help most? Least? What novel side effects emerge? Everyone freely modifying protocols undermines that.

Question

Jennifer, regarding FDA Phase IV and post-approval monitoring – what infrastructure exists? Look at the explosion of ketamine clinical work absent data coordination. What learnings apply to gathering MDMA insights at scale? Also, all trials use synthetic psilocybin – what do you know about natural psilocybin cost and FDA stances given manufacturing versus organic sourcing?

Jennifer Mitchell

Through my California research advisory role, I’ve seen protocols with natural psilocybin. The issue is evaluating crop quality – screening for adulterants or pollutants. That testing surprisingly raised natural production costs above anticipated benchmarks, hurting hoped-for cost advantages. But regarding specifics around psilocybin sourcing and FDA perspectives, Elliott likely knows more.

Elliot Marseille

Reinforcing Jennifer’s point – it’s harder to control dosing consistency with natural psilocybin given more variability without extensive testing. All current trials utilize synthetic psilocybin. And while manufacturing costs are pretty marginal, ultimate pricing depends more on packaging, marketing, and distribution – not production outlays.

Jennifer Mitchell

I wish a MAPS representative was here to better discuss predicted REMS requirements related to Phase IV post-approval MDMA/PTSD monitoring. FDA often mandates continued data gathering on drug usage, safety, and efficacy to inform future labelling changes. We’re all very interested in learning more about what information they’ll request and how MAPS structures Phase IV data coordination.

Question

As a public health student, I’m considering psychedelic access for marginalized communities like indigenous populations with these ancestral ties. Do you see traditional healers as valuable contributors to developing culturally-informed care models, given existing communal ceremony contexts integrating elders and youth?

Jennifer Mitchell

FDA is actually funding research by our colleague Dr. Brian Anderson evaluating longstanding community psychedelic use – including outreach to indigenous and spiritual groups to understand safe administration approaches used successfully for generations. We have much to learn from those communities and I hope for continuing dialogue to optimize this treatment paradigm shift.

Elliot Marseille

This question touches on a deeper one – are we progressing medicine or enabling connection with the divine, however one may define it? Traditional ceremonies largely focused on the latter, whereas current frameworks target psychiatric healing like PTSD and depression relief over spiritual contact. Yet what excites me most is the impending “natural experiment” – millions gaining access to previously scarce profound experiences, with hard-to-predict ripple effects. I believe it will be largely positive, but we must have proper safeguards against casualties or delusion, where time-honoured indigenous ceremonial “containers” can guide modern practice.

Imran Khan

Our Western health model defines wellness simply as the absence of diagnoses. Psychedelic research prompts questions about achieving human thriving or “betterment.” Can future health economics somehow measure that?

Elliot Marseille

There’s extensive research already on holistic psychedelic impacts beyond diagnostics – evidence for anti-inflammatory effects, enhanced immunity, lower cardiovascular disease risk as well as increased compassion, connection with nature, self-efficacy, etc. So modeling population-level wellness influences would be important. I’m working with interns reviewing existing literature focused on MDMA’s non-clinical impacts and collaborating with a European group doing the same for traditional psychedelics. Once we understand those holistic effects better, they can be incorporated into health economic modelling.

Question

Some startups are developing non-hallucinogenic psychedelic analogues – seeking to retain therapeutic efficacy while removing the “trip.” Does that approach have economic viability given high base psychedelic costs and minimal therapy cost shares?

Jennifer Mitchell

Compounds engineered without hallucinogenic properties would likely follow more of an SSRI regulatory pathway. You’d have to compare accordingly.

Elliot Marseille

It’s a deep question – what degree of benefit comes purely from pharmacological psychedelic action versus subjective phenomenological effects like insight? Some ketamine approaches care only about getting the compound to the brain with minimal “distraction” from psychoactive properties. But it could be both mechanisms contribute. I think it’s likely both. But if you can strip the trip while retaining antidepressant efficacy, some patients may prefer that.

Question

I participated in underground psychedelic therapy here 40 years ago, including blindfolded 8-hour sessions. How do you address placebo controls today with MDMA trials?

Jennifer Mitchell

While most MDMA session participants correctly guessed their assignment, placebo cases were less clear. Perhaps 8 hours with music, eyeshades, and attentive therapists could feel somewhat psychoactive for some. We invite inward focus – unlike recreational settings fostering external engagement like Burning Man. Controlling setting and set allows separating pharmacological impacts.

The participants in the MAPS studies didn’t have to be psychedelic naive. There were some restrictions around how many times and how recently they had taken psychedelics, but they didn’t have to be psychedelic naive.

Question

Appreciating distinctions between PTSD and complex PTSD – have differences emerged around treatment response or economics?

Jennifer Mitchell

We wondered if multiple or developmental trauma would prove more resistant to MDMA-assisted therapy. But intriguingly that wasn’t the case – similar for dissociative PTSD where patients detach during trauma discussion. So very welcomed news thus far.

Question

Have animal studies been required for FDA psychedelic approvals? Will natural versus synthetic sourcing require duplicate safety data?

Jennifer Mitchell

Phase I psychedelic evaluations have included animal testing, though psilocybin’s fragmented industry may complicate mutual data reliance across different products. Unsure if duplicative natural/synthetic safety assessments will be needed.

Imran Khan

Final words: if people can take away one thing from what you’ve shared today, what would you like that to be?

Elliot Marseille

I’m concerned by the normalization of extremely potent psychedelics like 5-MeO-DMT now available at dispensaries absent appropriate safeguards. Of course, I don’t want criminalization. However, I worry we lack societal structures to prevent casual recreational adoption without well-considered integration. My son recently referenced Chögyam Trungpa’s Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism – it’s far too easy to warp even profound experiences into ego inflation. While destabilization will occur for some, even in therapeutic contexts, we must support those individuals while also confronting potential backlashes strategically.

Jennifer Mitchell

I echo anxieties around widespread de-regulation without first understanding environmental interplay further. Haphazard 1960s access sparked lingering fallout impeding current medical acceptance. And while decriminalization has merits, making 5-MeO-DMT readily retail-accessible seems premature given lingering knowledge gaps around safe navigation.

Become a psychedelic insider

Get a Pro Membership to enjoy these benefits & support Blossom📈 full reports on Topics & Compounds

🧵 full summary reviews of research papers

🚀 full access to new articles

See Memberships