The Nature of Drugs – Volume 2 – by Alexander ‘Sasha’ Shulgin gives you a deep dive into the excellent lecture series that Sasha gave in the late ’80s. The lectures provide an overview of how the body works and how drugs (including psychedelics) influence it. Throughout the book, you are greeted with a positive attitude, an alchemic way of teaching, Sasha’s joking demeanour, and poignant criticism of drug laws that would still apply today.

A review copy was graciously provided by Synergetic Press.

If you want to help preserve the legacy of the Shulgins, please consider donating to the Shulgin Foundation. The nonprofit organisation is dedicated to preserving the legacy and work of Ann and Sasha Shulgin. They are committed to carrying forward their values by promoting education, research, and harm reduction around psychedelics and psychoactive substances while fostering community and connection.

Summary Review of The Nature of Drugs

Author: Floris Wolswijk is the founder of Blossom. He started Blossom in 2019 to help translate psychedelic research to a broader audience. Since then, he has grown the database to encompass 2000 papers and hundreds of other valuable resources. Floris has an MSc in Psychology and offers psychedelic-assisted coaching at FLO.

Introduction

The lecture series presented here is the second semester of Sasha’s introduction to pharmacology, delivered initially at San Francisco State University in 1987. Transcribed from the original lectures, this book continues examinations of dozens of compounds across lectures 9 through 23 of the course.

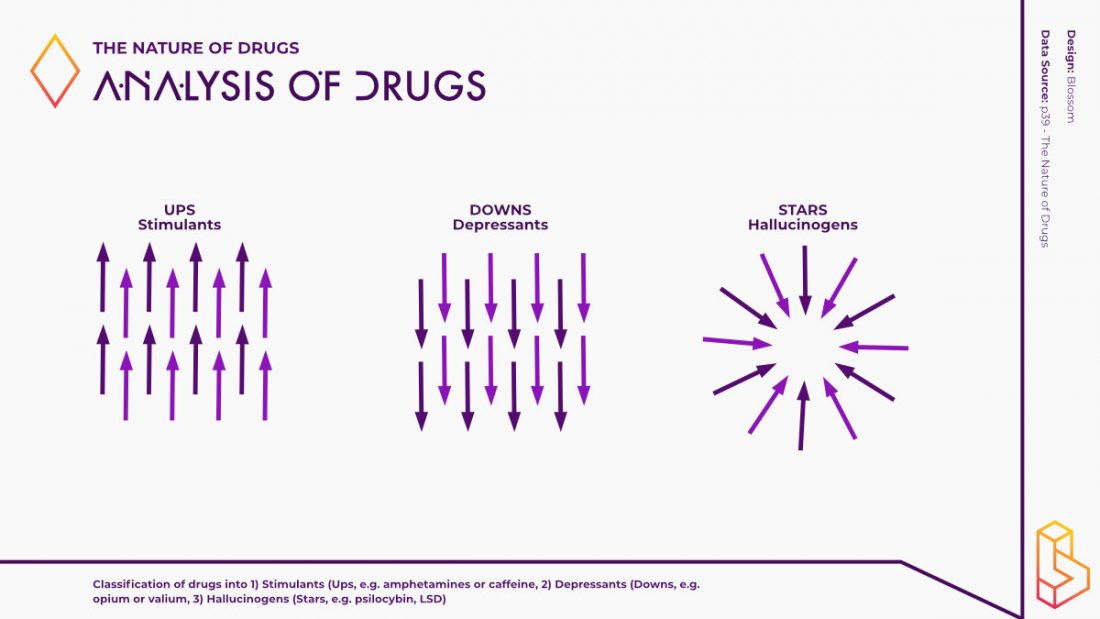

Building on the introductory lectures in The Nature of Drugs, Volume 1, this second volume contains extensive detail on stimulants, depressants, psychedelics, and more. We first join Sasha in discussion of stimulants (e.g. speed), then move to depressants (e.g. morphine), before an in-depth expose is given on psychedelics over multiple lectures.

Though the lectures follow a structured numbering and categorization, Dr. Shulgin’s engaging style shines through. Expect amusing anecdotes, diversions into history and society, and plenty of compound “show-and-tell” as he jumps around topics. Sitting in the classroom would undoubtedly be a thrill. This series offers us the next best way to grasp the magic.

The Nature of Drugs presents the story of humanity’s relationship with psychoactive substances from the perspective of a master psychopharmacologist. Shulgin examines subjective effects, social stigmas, pharmacology, legal policies, and uses of compounds throughout history with an honest and agenda-free approach aimed at educating readers without chemistry backgrounds while still engaging experts in the field.

In this review, I’ll share key lessons from the lectures. But as Sasha advises in the first series, look deeper than the factual data. Read between the lines and absorb his passion for this life’s work that unfolds across these seminal lectures.

Lecture 9 – Stimulants I

When thinking about nerves in the body, a counterintuitive observation must be made. Not all nerves activate; some don’t do anything, whilst others actively suppress stimulation. Through this lens, sleeping is an active (serotonergic) process.

Getting more messages to fire between cells (across the synaptic cleft) can work by making the transmission go 1) better, 2) more often, or 3) more easily. For instance, stimulants can work by removing things that clear out the transmitter. Or they can work by inhibiting the reuptake (cocaine). Or it can help release signals (‘releasing agents’; amphetamines).

Sasha – through Andy Weil – argues that many plants have protections built-in against the abuse of the ‘active’ compounds. Opium will have you vomiting before you’re as high as you can be after injecting heroin. The peyote plant contains many other alkaloids next to mescaline.

The same may be said about caffeine, a coffee and tea component. The lecture discusses these substances, showing how the different molecular structures are similar.

Lecture 10 – Stimulants II

If you look at global use, tobacco is one of the most addictive things out there. The main culprit is nicotine. When your body breaks it down, it’s ‘metabolised’ into the inactive metabolite cotinine.

Nowadays, the most common way of using tobacco is smoking. Before the invention of cigarettes, it was used orally (via the mouth or nose). Used orally, tobacco is a powerful stimulant (for a brief example, see the first episode of How To Change Your Mind on Netflix).

Lecture 11 – Stimulants III

Cocaine is the last stimulant being discussed. Sasha gives an overview of the origins (coca leaves with 1-2% cocaine), the vast amounts being produced (100,000 pounds of leaves annually), and how it can be converted into longer-lasting effects (crack cocaine).

Commenting on the laws at that time (still relatively unchanged), Sasha wonders at the much higher penalties on crack cocaine, whilst chemically, the compound is identical to cocaine itself. “The whole idea of writing an entire law about cocaine, then a whole second law about freebase, and now a while third law about crack doesn’t have scientific validity.” He also argues that much of the damage from drugs is a result of their illegality. He even states that the popularity of some drugs follows the banning of other (possibly less harmful) drugs.

When testing for drugs, the test usually does not look for the drug itself but its metabolite (as the drug is no longer there). In the case of cocaine, this is ecgonine.

Hinting at the next few lectures, Sasha notes that with chronic use, cocaine can become a depressant (instead of a stimulant).

At most lectures, samples are available (in vials) so students can see the discussion topics first-hand. I won’t comment on this in other chapters, but the final words of the lecture amused me: “please don’t take them with you.”

Lecture 12 – Depressants I

Possibly just as many people (in the US, but likely worldwide too) are dependent on depressants as there are on stimulants.

The most ancient depressant is the opium poppy. It was initially found in Afghanistan, Laos, Thailand, and surrounding countries (now also Mexico). As with tobacco, opium was taken orally (e.g. a tea combination of opium and alcohol named Laudanum) before it was smoked.

Sasha describes the smoking experience as: “There’s more of a fantasy, more of the dropping away instead of the alerting care, a dropping away into not caring that is part of the experience.”

Treatment of heroin addiction had, at a very early stage, been done by providing it via physicians (before 1920). But drug laws in the UK and beyond soon made this untenable (even to this day, being able to help those with addictions is fraught with legal difficulties). Methadone is a way of getting around this restriction, being a synthetic narcotic with a longer duration and less stigma attached (still being addictive, though).

Heroin has a half-life of about three minutes. The hours-long effects are thus due to the metabolites (in this case, active).

Lecture 13 – Depressants II

This lecture covers fentanyl and the even more potent variations that have been since made. It also discusses the effect of depressants (or any drugs) using the term ‘intrinsic’. If the effect is intrinsic, it means the drug in its own right does what the drug appears to do, versus converting first into the active metabolite (or with even more steps in between).

Sasha also describes the limits of cross-species research. Some substances that are toxic to other mammals might no affect us humans (that much) or the other way around.

Lecture 14 – Depressants III

The last lecture ended with a short discussion on alcohol and the ‘proof’ level (alcohol percentage x2). This lecture starts with a discussion about solid alcohols (e.g. barbital and phenobarbital). With alcohol, the line between ‘good’/active and deadly levels is very thin.

The discussion then moves to the level of alcohol and how you can measure it at different points (e.g. blood, urine). And finally touches upon the related compound that goes by the name Qualudes.

Lecture 15 – Intoxicants

Nitrous oxide (laughing gas) is the first compound that is discussed in the intoxicants lecture. When used in dentistry and within a therapeutic framework, it’s mixed with 50% air; without it, you would die.

Other intoxicants, such as poppers and ether, are briefly discussed, including their historical use of them.

Then, we get a glimpse of the first (broadly defined) psychedelic, MDA. This molecule can be made by taking safrole and adding ammonia to its active position. “Myristicin from nutmeg is one molecule of ammonia away from MMDA”. In the handout, several other psychedelic compounds based on essential oils (from plant sources) are listed.

Lecture 16 – Deliriants

Sasha discusses the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the autonomic nervous system. The adrenergic (adrenaline) system only applies to the sympathetic branch. However, the cholinergic (acetylcholine) system applies to both branches.

When a substance knocks on the door of the blood-brain barrier, it can only go true if they are uncharged. But some drugs (e.g. amphetamines) get around this by losing the charge and then picking it back up in the brain. The same is true for acetylcholine.

This relationship is further explored before moving on to deliriants like ketamine and PCP. Sasha describes them as “separating the mind and body”. Sasha describes his own experience with PCP and his general distaste for compounds that disconnect him from his body (vs being more connected to it). He also briefly mentions John Lilly and a couple who used ketamine daily (alas, the wife was found dead under mysterious circumstances).

There is a discussion with the students about this ‘compulsive’ use of a drug. It can be likened to someone getting the positive effects, but after the first few times needing more and more to get the positive effects, and then later only using it to go back to ‘normal’ before dropping off into negative territory again.

So, although there are few (but still real) physical negatives associated with ketamine and PCP, “psychologically people get into very difficult dependencies”.

Lecture 17 – Peyote

Peyote has been used for over 2000 years within the Aztec culture. Some tribes, specifically the Huichol, make a pilgrimage yearly to find the peyote buttons. Nowadays (in the 2020s), this practice has become problematic as much of the peyote is used for other people than originally, depleting the available stock.

The myth of peyote states that it originates from a deer (a sacred animal to the Huichol). From the antlers of the dear, the peyote originated, from which came corn.

Sasha then describes the pilgrimage between October and November each year and concludes with several days of eating the peyote buttons. He also notes the use of peyote in long-distance running, which may be beneficial.

The ritual itself is very spiritual but has few religious overtones. Still, to gain religious protection, the Native American Church (NAC) was started.

Sasha then describes the ritual in detail, including the vile taste of the buttons and the trip’s 8 to 10-hour length.

Louis Lewin was the first to isolate mescaline and four other major alkaloids from mescaline.

A detailed description of the effects can be found in The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell by Aldous Huxley.

For Sasha, mescaline was the first psychedelic he had experience with. It launched his research career: “I found it to be a captivating attention grabber, because I was seeing things, interpreting things, getting into a relationship with what was around me, both in the visual sense and in the intellectual philosophical sense, that was impossible to rationalize as being the result of using a few hundred milligrams of a 25-atom molecule. So where does all this come from? Well, obviously, it’s all stored away up in there [pointing to his head]. The skill is in there. The ability is in there. The interpretation is in there. And this was catalyzing its release. And so, I said, “My golly, if that simple molecule can do it, what other simple molecules could catalyze my access to other aspects of myself?” And that is what launched my research work 30 years ago, and it has not been answered satisfactorily yet, so I’m still in the middle of it.”

Lecture 18 – Psychedelics I

Phenethylamine is a specific compound; slight variations are often called ‘phenethylamines’. An example of this is mescaline, a substituted phenethylamine.

Sasha then touches upon a very important aspect of the metabolism of drugs. At different dosages, different ways of metabolising it are going on. At a very low dose, it could very well be totally metabolized; at a very high dose, it could overwhelm a system to kill the host. In other words, there are different ways of handling compounds, and each can be saturated. The scientific literature describes this as the ‘structure-activity relationship’.

Guessing the drug’s potency isn’t possible (Sasha argues); therefore, when testing novel compounds, he always starts at 100x lower dose than one would reasonably expect effects.

“All compounds are unique, all actions are unique, all chemical entities are unique.”

Sasha describes the experience of testing a compound by telling the (lack of) effects of different TMA configurations (trimethoxyamphetamines).

One psychedelic that had been distributed at that time was DOM, known under the street name STP (serenity, tranquillity, and placidity). The big issue was that the dosage of 20mg was much higher than the optimal dose, and the onset took quite a while (so people took 2-3x this already high dose).

MDMA is the next psychedelic up for discussion. The molecule was first used mainly in psychiatry (therapy) but has found its way into widespread use (and in Schedule I).

Lecture 19 – Psychedelics II

This lecture continues with a discussion about MDMA and its being put in Schedule I (‘high potential for abuse’ and ‘no medical utility’). The same goes for THC, both may be (partially) rescheduled in the coming years (that is, 30+ years later).

Sasha dispels the myth that MDMA was patented as an appetite suppressant; it was just patented because Merck researchers discovered it (1912, composition of matter patent in 1914).

The first mention of MDMA after this comes from research published in 1970 but done in 1955 at the University of Michigan (paid for by the US Army). The goal of the research was to find a compound that could be sprayed on the enemy to incapacitate them.

The clinical use of MDMA started between 1977 and 1981. At that time, the drug was often also taken by the physician (and the patient).

“I would estimate that by the time the first legal actions were taken, it was probably used by literally thousands of psychiatrists and psychologists, from what I can gather, in virtually all the Western countries that I have been able to get information from.”

MDMA use has side effects, and some of those are discussed, including raised blood pressure and jaw clenching.

2C-B and DOB get a mention, both also in relationship to the Designer Drug Law (Analog Bill).

Then ayahuasca (and DMT; and 5-MeO-DMT) and psilocybin are discussed very briefly.

Lecture 20 – Psychedelics III

This lecture covers indoles (e.g. DMT, bicyclic structure, consisting of a six-membered benzene ring fused to a five-membered pyrrole ring) and, for the larger part will also remark on the concept of drug usage itself.

Indoles target the serotonin receptors (versus the focus on dopamine, norepinephrine/epinephrine, and adrenaline/noradrenaline for phenethylamine).

Set and setting refer to the mindset (preparation) that you bring into the experience and the environment where the experience takes place. “Both will profoundly influence the type of experience that is had. It can profoundly influence your physical response to the drug.”

Sasha also discusses the religious-cultural use of a drug and how that set and setting greatly influences how a drug is experienced. Even how the use of a drug is culturally accepted or not (e.g. “So [the male members of the Jivaro tribe] are stoned all the time. They are. They use [ayahuasca] Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday. One in four of the male members of the Jivaro are shamans, and probably more are who won’t admit it.”).

Besides historical and ethnographic accounts, examples from early psychedelic research are also given. One striking example is a study where 90% of participants wouldn’t want to repeat the LSD experience. In other words, that set and setting was not what we expect of LSD nowadays. This is contrasted with another experiment (in a much better living room setting) where 85% would repeat the experience.

Sasha then gives some sage advise on how to help someone who’s going through an unexpected psychedelic experience: “Join them! Don’t tell them lies; they’ll see through it. The cognitive structure is totally intact. … Don’t say, “You will be all right.” How do you know if they will be all right? You don’t know. So don’t say it will be all right. Just say, “I’ve been there. And let me tell you, it’s got some rough spots and got some interesting spots.” Join them, walk. Be with the person. Get into that territory. Let them begin relating back to you and walk with it. Then tide them over until the body takes care of it, metabolically the liver chews this up and pees it out.”

Lecture 21 – Prescriptionals

The beginning of this lecture dives deeper into LSD, a synthetic compound made from lysergic acid. In a sense all the compounds originate in nature, but making LSD from the origin will take about 500 steps. LSD also got put in Schedule I, and one of the motivating cases revolved around a suicide which was linked to LSD use – 6 months earlier.

In 1987, the money that was being spent on the top 5 prescription drugs was north of $1 billion (for ulcers, hypertension, high blood pressure, and a diuretic). All could be said to be related to the symptoms of stress. If I make a guesstimate of the current top selling drugs, that would be $32 billion ($1 in 1987 is equivalent in purchasing power to about $2.71 today).

The market for psychiatric drugs was only just getting started around the time of the lecture series. Sasha remarks on the indication of ADHD (ADD/minimal brain syndrome) or the prevalence of stress clinics (using Quaaludes to relieve it). Remarking on the mega amounts that one doctor was prescribing (50% of total sales), it is clear that legal system abuse also happens (leading to the rescheduling of methaqualone – the chemical name of Quaaludes – from Schedule V to II).

The development of new drugs used to cost $25 million (say $70 million in 2023 dollars), but had back the already ballooned to $200 million (nowadays estimates are closer to $1 billion). And remarking on what drugs are being developed, “All companies thrive on what’s called “chronic medication”.

Lecture 22 – Cannabis

What if addiction could be split out into physical and psychological dependence? Sasha ponders this question based on a Playboy article a student gave him earlier. He wonders if there is an ‘addictive personality’ and that it doesn’t matter if they take drug A or B. I think that over the last 35 years, our thinking about this has evolved a lot, especially with the focus on trauma as an underlying cause.

Sasha recounts the many loopholes he had to jump through to get a licence to grow cannabis/marijuana legally. He talks about the five licenses he needed to have and how authority (e.g. government institutions) hold on to the authority bestowed on them. He shares two sage pieces of advice: 1) “Don’t fight the system – use the system,” and 2) “[a friend said] that if you are a threat to the system, but you’re not known to be a threat, you’ll be left alone.”

The latter part of the chapter describes the story in more detail and gives a terse overview of terpentines, THC, and CBD.

Lecture 23 – Cannabis & LSD

The final lecture touches on several subjects related to the identification of drugs, providing witness testimony, and cannabis & LSD.

The idea of flashbacks is discussed, noting that it’s not a ‘drug’ phenomenon but more likely a rekindling of clues that activate the nervous system and the brain. In contrast to LSD, THC and PCP stay in the body for longer (in the fat tissue), but that doesn’t mean it will be psychologically active.

With LSD, the effects are half as strong if you’re doing the same dose the next day (refractoriness). Thus, Sasha expects one only to be able to do LSD twice a week if one wants to get the full effects from the same dose (one could also double the dose on back-to-back days).

Through this seminal lecture series, Sasha Shulgin provides a captivating journey into the nature of drugs. His passion for the subject matter shines through on every page as he dives deep into the pharmacology, effects, cultural contexts, and legality surrounding dozens of psychoactive compounds.

Shulgin approaches each substance without judgement, seeking instead to educate audiences on the full spectrum of considerations for every chemical. His criticisms of drug policies remain poignant decades later. And his arguments for proper set and setting when using psychedelics ring just as true today.

For anyone seeking a broad understanding of how drugs interact with the mind and body, The Nature of Drugs lecture series offers an unparalleled resource. We journey along with the godfather of psychedelics himself across these 23 lectures that so adeptly balance scientific rigour with compassion and wit.

The book provides deep insights into our complex relationship with chemical compounds that alter consciousness. If the overview has piqued your interest, I highly recommend getting a copy of the full lectures to soak in Sasha’s alchemical wisdom.