To better understand the science of psychedelics, and how we can make the bridge to implementing them in practice, Blossom is conducting a series of interviews with psychedelic scientists. Our editor-at-large, George Fejer, speaks to David Glowacki, one of the world’s leaders in the use of virtual reality applied to scientific simulation and visualization.

Key Insights

- Virtual Reality can be used as a powerful tool for inducing mystical-type experiences that are comparable in their intensity to moderate doses of psychedelics. With the so-called Isness protocol, people’s bodies are transformed into energetic essences, and this can have a transformative impact on how they perceive themselves in relation to others and to the world

- The experience of dissolving your physical body into energy can also aid social interactions by diminishing the force of ego, coaxing people to let go of those things that typically colour social interactions (age, appearance, class, etc)

- VR has the potential to be a useful tool for aiding preparation and integration before and after psychedelic therapy, or as an adjunct for increasing the subjective intensity of low doses

Author: George Fejer is a freelance scientific writer and a team coordinator of the ALIUS network for consciousness research. He studied Cognitive Neuropsychology (M.Sc.) and Bioscience (B.Sc.) and researched the effects of psilocybin microdosing on perception. His current work compares the phenomenology of serotonergic versus anticholinergic hallucinations using a mixed qualitative and quantitative methodology.

Expert: David Glowacki (Ph.D., M.A.) is a cross-disciplinary researcher, with interests spanning computer science, nanoscience, aesthetics, cultural theory, and spirituality. In 2008, he completed his Ph.D. in molecular physics. He is one of the world’s leaders in the use of virtual reality applied to scientific simulation and visualization. He is the founder of the ‘Intangible Realities Laboratory’ (IRL) which applies virtual reality at the immersive frontiers of scientific, aesthetic, computational, and technological practice. Recently, he published the so-called ‘Isness’ virtual reality protocol which can elicit mystical-type experiences that are comparable in their intensity to moderate doses of psychedelics.

New perspectives on reality through VR

George Fejer

Hello David! Your current research entails working with virtual reality (VR) to induce mystical-type experiences whose intensity is consistently rated as potent as a moderate dose of psychedelics. But I understand you have a background in computational chemistry, and you further describe yourself as a scientist, an artist, and a cultural theorist among other things. Could you elaborate on your background and how you made the leap from molecular simulations to mystical consciousness?

David Glowacki

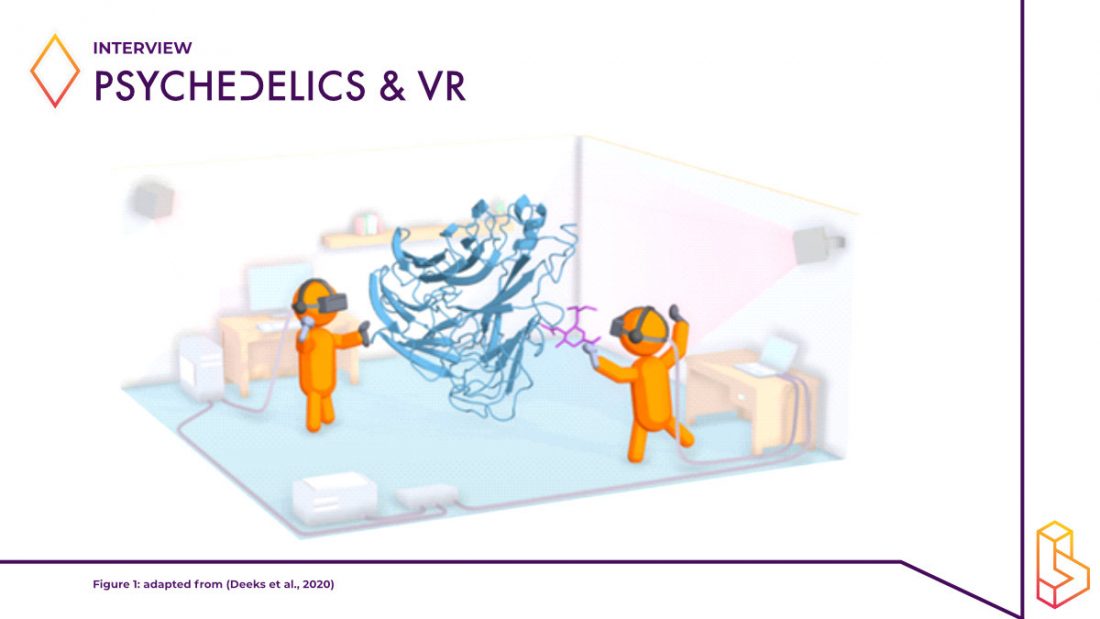

As you mention, my original Ph.D. training was in computational molecular physics and I founded a laboratory called the Intangible Realities lab (IRL) where we developed immersive technology for scientific simulation and visualization. Over the years we developed an open-source virtual reality (VR) framework to simulate and visualize nanoscale realities and molecular objects in real-time (Deeks et al., 2020). This enables researchers to manipulate atoms and molecules as if they were tangible objects by reaching into real-time simulations of a physical system.

It is important to understand that the laws that govern how atoms and molecules move follow quantum mechanics, which is a theoretical and philosophical framework that tells us that what we think of as fixed material reality is in fact energetic in its essence. At a fundamental level, quantum mechanics describes matter not as a discrete and localized object, but as blurry waves of energetic essences.

In school, you may have been taught that molecules are like plastic objects connected by sticks, but this is just completely wrong and not how physicists think about them. And so we have been using virtual reality to simulate energetic visualizations of molecules where people could use their hands to manipulate them in real-time. It turns out that people were having very profound experiences in what was originally designed to be a scientific visualization framework.

George Fejer

When people like your colleagues encounter this virtual reality, do these experiences transform their worldview and how they think about matter and energy?

“In school, you may have been taught that molecules are like plastic objects connected by sticks, but this is just completely wrong and not how physicists think about them.”

David Glowacki

Clearly, it does! At least it seems to have helped them unlearn their conventional way of thinking about matter as a fixed entity by experiencing it as an energetic and dynamic process. Since you cannot see molecules with the naked eye, scientists use abstract representations, such as mathematical equations, to make sense of what they are and how they work.

By making this abstract information available to our phenomenological senses we are enabling researchers to experience otherwise invisible realities. This had a real impact within the scientific community, as many of my colleagues have reported that it expanded their imagination and in some cases has altered the way they conduct research.

Similarities between VR and psychedelics

George Fejer

How did you discover that these experiences are similar to psychedelics?

David Glowacki

First of all, we started analyzing a lot of phenomenological accounts of people who had drug-induced and nondrug-induced mystical-type experiences. For example, people often report having transformative experiences in the context of meditation. But it happens in other contexts also: the neuroscientist Jill Bolte Taylor describes how a left-brain stroke transformed her perception of reality in a beautiful TED Talk.

A common theme that emerges from various types of transformative and spiritual experiences is that people gain a perceptual sensitivity to the energetic nature that is underlying matter all around us. You can find this in several spiritual traditions talking about the aesthetics of luminous energy that underpins all things. For instance, various meditation practices are based on visualizing yourself and others as forms of energy.

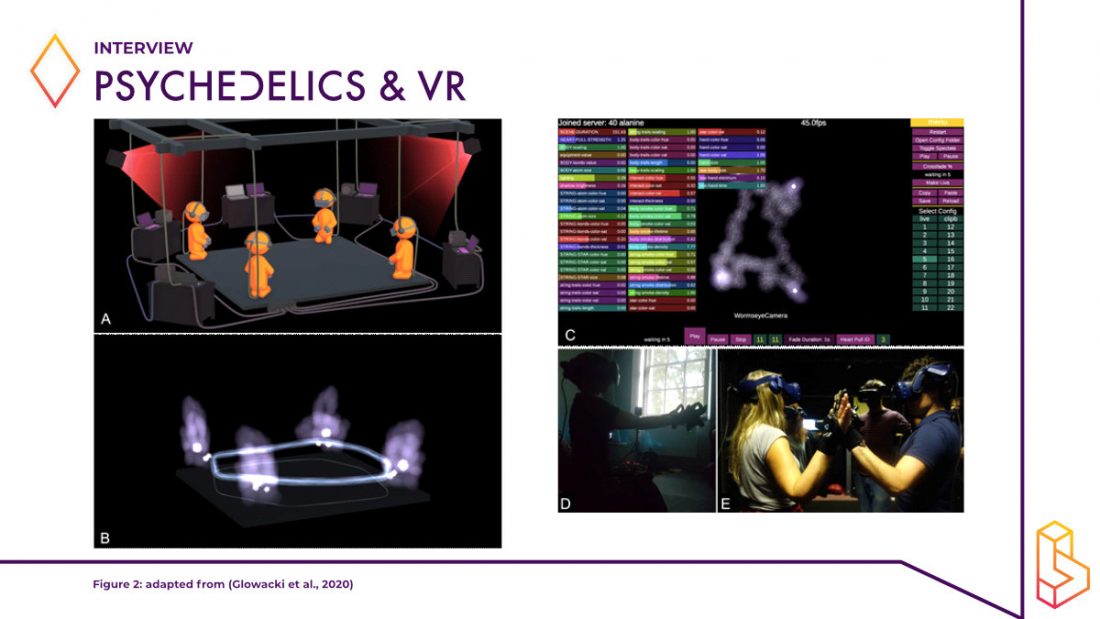

We realized that there was a synergy between these phenomenological accounts of energy and our quantum mechanical simulations of energy. Essentially, we combined our scientific VR framework with a new narrative arc that was designed to help people to meditate on the fundamental nature of energy. We then set out to design mystical-type experiences within a VR protocol which we developed – entitled “Isness” – and found that people’s experiences were comparable drug-induced and nondrug-induced experiences with respect to their transformative potency (Glowacki et al., 2020).

I coined the term “Numadelic” to describe such experiences. It is derived from the Greek word Numa which means spirit. Similar to psychedelics, which means mind-manifesting, these experiences manifest the spirit by letting people experience the luminous qualities of their energetic essence.

Mystical experiences and their value

George Fejer

It is interesting to see that you could draw parallels between a discourse within physics, about the nature of light and energy, and apply it to an outer domain to induce mystical experiences. But there is also a discourse about mystical experiences that dates back to William James and philosophers like Walter Stace. Have any of these thinkers influenced your work and how you designed your Isness protocol?

David Glowacki

I have a Master’s degree in religious studies, so I have been aware of William James as an incredibly important figure for comparative religion and the psychology of religion since the early days of my studies. But I had not been aware of Walter Stace until I started looking into how mystical-type experiences were measured and stumbled upon the research on psychedelics by Roland Griffiths at Johns Hopkins University. Over the last decade, the Hopkins group has collected data from thousands of participants and compiled a comprehensive dataset about the dose-response relationship between psychedelics and mystical-type experiences. After becoming aware of this, I became interested in measuring the potency of virtual reality experiences using the same questionnaire, but the Mystical Experience Questionnaire itself was not a template for designing Isness.

The Isness aesthetics is also influenced by a personal near-death experience I had while hiking in 2006 when I fell thirty meters and suffered multiple broken vertebrae, a broken hip, and a thoracic contusion. While I was waiting for the rescue helicopter to pick me up, the blood from my heart was leaking into my lungs. Every breath became a struggle, and I could feel that I was slowly suffocating. It was clear to me that I would not be able to continue breathing, and for three or four hours, I was preparing for the transition from this life to the next.

With my body completely broken, I felt my conscious awareness separate from my body. I perceived my body as a light whose intensity grew stronger with each inhale and diminished with every exhale. I had a real sense that this light was my own life force and that it was diminishing with my imminent death. I was eventually rescued via helicopter, underwent multiple surgeries, and spent a long while recovering in a wheelchair.

The only other time I had a comparable experience to this encounter with death was when I took LSD for the first time. These experiences formed the aesthetic foundation for “Isness”. The algorithms are grounded in a physics-based matter-energy paradigm, but the aesthetic design is inspired by my near-death experience.

So I think it makes sense that Isness resonates with people – because I am probably not the only person to have had such experiences. Other people probably have these types of experiences in their spiritual practice, during meditation, and in response to psychedelic substances. These different classes of experiences fall under the larger umbrella term of mystical-type experience, and it makes sense that they can be measured consistently and reproducibly via questionnaire.

George Fejer

There is an ongoing discourse within the psychedelic research community (e.g. Sanders & Zijlmans, 2021; Strassman, 2018) which often criticizes the term ‘mystical’ for not being scientifically neutral to a sufficient degree. Do you have any strong opinions on this topic?

David Glowacki

When we use the Mystical Experience Questionnaire (MEQ) our main objective was to measure it the same way people measure psychedelics, and this questionnaire provided the most comprehensive data set to determine where our design falls within that spectrum of experience. I only realized that the term mystical-type experience was a controversial thing after I wrote the first Isness paper.

Regardless of its controversial title or other shortcomings, it is the most systematically applied questionnaire to gather data across thousands of participants. Other people call it a peak experience, a unitive experience, or a transformative experience. But in my opinion, these all fall into the same cluster, and my view is that it does not matter so much how you choose to label them.

George Fejer

But since you also have a background in religious studies, are you satisfied with what the MEQ is measuring? Some people may argue that the construct is culturally biased, whereas others see it as a universal experience that can be measured consistently across everyone. Could you elaborate on your position on that?

“Perhaps mystical experiences can help us to understand the limits to our conventional ways of interpreting the world.”

David Glowacki

I do not have a fixed answer to that question, but I can share some reflections. One of the things you encounter during mystical experiences is the sense that this phenomenological reality is not necessarily the end of the story, and there is a lot more of which we cannot necessarily conceptualize. It is as if the different ways in which we conceptualize our experiences are just one small aspect of a rich cosmological tapestry.

The representational conventions and categories that we use to dissect, classify, and analyze our experiences are kind of arbitrary. There are a lot of ways in which it could be done. When we become locked into just one way of constructing our reality, it can cause a lot of suffering. Especially if you attach your identity to a fixed idea of the world, only to discover that things do not always fit this model. And so mystical experiences give you a glimpse into this arbitrariness and the realization that there are many different ways to view reality.

The term mystical hints at the idea of a “mystery”, which is a concept that science fundamentally struggles to embrace. I think that is why there is discomfort with the word mystical because it implies that there is ultimately something we cannot know, and science in its modern incarnation struggles with the idea of mystery. Personally, I think that the sciences should become more comfortable with the idea of mystery. For instance, the bulk of the universe’s dynamics are driven by dark matter, an entity we cannot see, do not know what it is, and cannot describe. Perhaps mystical experiences can help us to understand the limits to our conventional ways of interpreting the world.

Experiencing ‘Isness’

George Fejer

Indeed, the limits of our understanding already start at the level of explaining what conscious experience is if we define consciousness as the subjective quality of what it is like to be, a bat for instance (Nagel, 1974). Bats have a different set of phenomenological senses, so their subjective experiences are ineffable to us. Do you think the profoundness of VR comes from the fact that it could be used in such a way that we can experience what it would be like to be a bat? What do you think makes Isness so profound for many people?

David Glowacki

What it’s like to be like something depends on the form of the body and the perceptual inputs, which is radically different for bats. They experience very distinct parts of the electromagnetic spectrum than us, they process light and sound differently, they have wings, etc. I would never claim that VR can give us access to all of that or that it can simulate any type of experience along those lines.

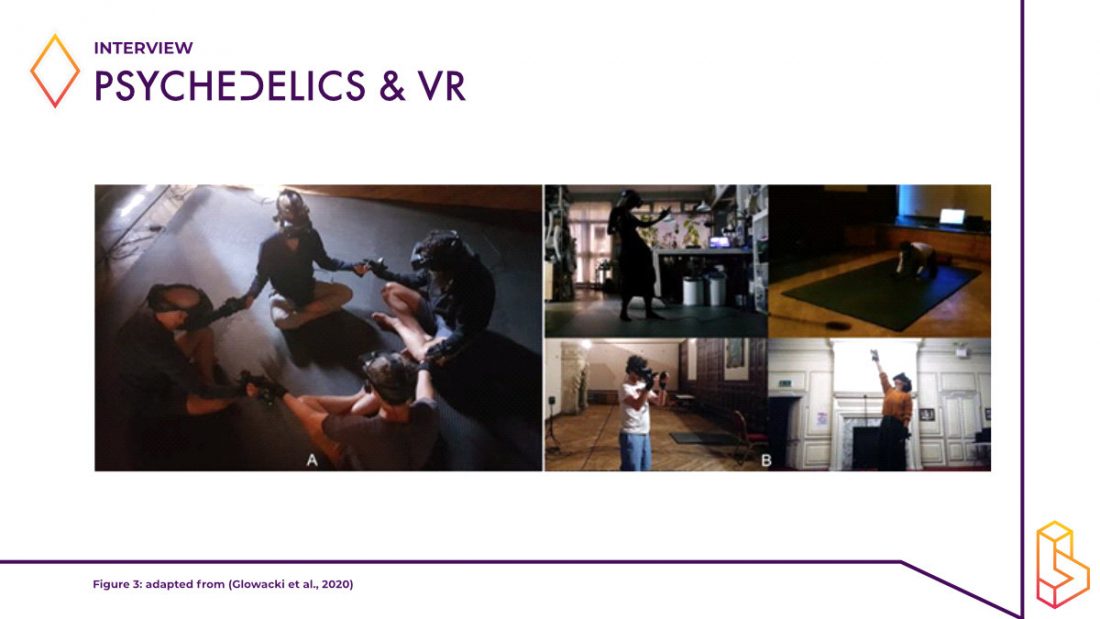

But what we can do is dissolve the human form into energetic essences, which gives people a profoundly different sense of what it is like to be themselves. This is also in line with Tibetan meditation practices wherein people imagine themselves as a form of energy that is continuous with their surroundings.

Preliminary evidence from our studies suggests that the experience of seeing yourself and others dissolve into light gives rise to a sense of continuity that is profoundly different from their typical day-to-day experiences. Seeing their bodies in a luminous representation, for example, suspends many of the ego games that people normally attached to perceiving physical bodies.

We find that people are not worried about how they look or how other people perceive their physical form, and they also stop judging the appearance of others. Since people are constantly trying to moderate their behaviour based on projections of what other people think about them, suspending these dynamics can often bring a sense of relief.

George Fejer

The opportunity to experience Isness together with other people is quite a recent development and it introduces social dynamics that seem to be in line with the idea that mystical experience can form a relation process (Roseman et al., 2021). What was your aim with making the experience available to multiple people simultaneously?

David Glowacki

Originally we developed this function to overcome restrictions of the COVID pandemic, but we know that the relational aspects are important. For example, people often construct their egos based on their social interactions with others. When the ego is no longer so prominent during social interactions, many people experience the difference.

The multi-person VR setup serves a crucial design function because it forces people to be conscious of how their ego operates differently when everybody has a luminous energy body. In the virtual environment, people can also experience their light body overlap with another person – i.e., their representation of self can literally include within it another person.

We used a measure called the “inclusion of self in community scale”, which has also been applied in psychedelic ceremony studies and found a strong effect post-Isness (Glowacki et al., 2021). The ability to literally overlap bodies is interesting and is associated with strong psycho-somatic sensations for many people. Even sexual intimacy – which is maybe the closest that bodies can get in a physical world – does not permit a 100% overlap with another body. As an artist and designer, I find it very exciting to work with virtual environments that enable access to experiences that are not available anywhere else, and which transcend their lived experience.

“We are interested to know whether VR could offer a replacement for psychedelics among patients who cannot use these substances for medical reasons, religious reasons, or cultural reasons.”

Scaling up psychedelic VR

George Fejer

What are your plans for making this technology available on a greater scale? Do you see a role for it within the context of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy?

David Glowacki

In order to expand access to our VR setup, you need a lot of cloud servers that are distributed across the world to make it possible for multiple people to dial in and interact with each other in real-time. There is a lot of technical work that would have to go into that infrastructure of making it accessible to multiple sites, but our open-source setup already works quite well.

With respect to psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, I recently teamed up with Joe Hardy and Greg Roufa to found a company called Anuma, specifically to work with clinics and therapists in the field. We do not think that VR could always offer a replacement to psychedelics, but we are interested in whether it can be an adjunct to preparation and integration sessions. If you look at the therapy protocol developed by MAPS, you notice that the bulk of the time is used for preparation and integration. We are particularly interested in whether the Isness framework could aid this process and help therapists treat multiple patients simultaneously. We would like to start doing systematic studies of cohorts whose preparation/integration involves VR and compare the outcomes to those which do not.

Another line of research of interest concerns the potential synergy of combining VR with psychedelics. It’s been shown that higher dose psychedelics can yield positive outcomes if it is managed appropriately in a therapeutic context, but it may also bare risks for certain people. We are wondering whether small doses combined with VR could yield similar results as very high doses.

Finally, we are interested to know whether VR could offer a replacement for psychedelics among patients who cannot use these substances for medical reasons, religious reasons, cultural reasons, etc. For example, Robin Carhart-Harris and I are working with a range of collaborators to develop a self-blinded citizen science protocol to investigate the difference between VR with placebo versus VR with low-dose psychedelics.

These are still open questions, and as I said, I do not claim that VR is the same as a psychedelic. But our work to date using the same psychometric tools used to measure psychedelic experience shows that people who experience Isness provide scores that are comparable to a moderate dose of psychedelics. Obviously, the experiences are not the same and they have different mechanisms, but by carrying out good research we can better understand these experiences and articulate the differences better. Hopefully, this can help us develop better tools to help people.

References

Deeks, H. M., Walters, R. K., Hare, S. R., O’Connor, M. B., Mulholland, A. J., & Glowacki, D. R. (2020). Interactive molecular dynamics in virtual reality for accurate flexible protein-ligand docking. Plos one, 15(3), e0228461.

Glowacki, D. R., Williams, R. R., Maynard, O. M., Pike, J. E., Freire, R., Wonnacott, M. D., & Chatziapostolou, M. (2021). Dissolving yourself in connection to others: shared experiences of ego attenuation and connectedness during group VR experiences can be comparable to psychedelics. arXiv preprint arXiv:2105.07796.

Glowacki, D. R., Wonnacott, M. D., Freire, R., Glowacki, B. R., Gale, E. M., Pike, J. E., . . . Metatla, O. (2020). Isness: using multi-person VR to design peak mystical type experiences comparable to psychedelics. Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

Nagel, T. (1974). What is it like to be a bat. Readings in philosophy of psychology, 1, 159-168.

Roseman, L., Ron, Y., Saca, A., Ginsberg, N., Luan, L., Karkabi, N., . . . Carhart-Harris, R. (2021). Relational Processes in Ayahuasca Groups of Palestinians and Israelis [Original Research]. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 12(300).

Sanders, J. W., & Zijlmans, J. (2021). Moving Past Mysticism in Psychedelic Science. ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science, 4(3), 1253-1255.

Strassman, R. (2018). The psychedelic religion of mystical consciousness. Journal of Psychedelic Studies, 2, 1-4.

Become a psychedelic insider

Get a Pro Membership to enjoy these benefits & support Blossom📈 full reports on Topics & Compounds

🧵 full summary reviews of research papers

🚀 full access to new articles

See Memberships