Adverse physiological reactions to psychedelics are rare. However, that doesn’t mean they can’t occur, even with the most meticulous preparation.

Adverse events can be divided into both physiological and psychological effects. Though psychedelics don’t have many negative physiological effects, we will go over these first and then discuss the potential adverse psychological effects.

Recent headlines were made about the biggest psilocybin-assisted trial for treatment-resistant depression, here we put the adverse events in context.

Physiological adverse events

Psychedelics can elicit physiological responses such as dizziness, weakness, tremors, nausea, drowsiness, blurred vision, dilated pupils and increased tendon reflexes, once consumed [1]. Increases in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure have also been reported [2]. As a result, researchers may decide to exclude participants from studies using psychedelics if their resting blood pressure is notably high.

Consequently, it is important that prospective trial participants undergo general medical screening before participating in psychedelic research. Trial participants should also make researchers aware of any other medications they are taking as these drugs can potentially interact with psychedelics and produce unwanted adverse effects.

For example, it has been reported that the acute administration of the SSRI fluoxetine can alter the psychedelic experience induced by LSD, even leading to a more potent experience [3].

Psychological adverse events

Most risks associated with psychedelics tend to be psychological rather than physiological. The most likely risk associated with psychedelics is known the world over as a ‘bad trip.’ A bad trip is characterized by anxiety, fear/panic, dysphoria and/or paranoia [4].

The effects of a bad trip cause a person to become frightened, have troubling thoughts about their life and other intense emotional experiences. These unpleasant thoughts and feelings can lead to dangerous behaviours in people, especially when they are unprepared for, or unsupervised, during the experience.

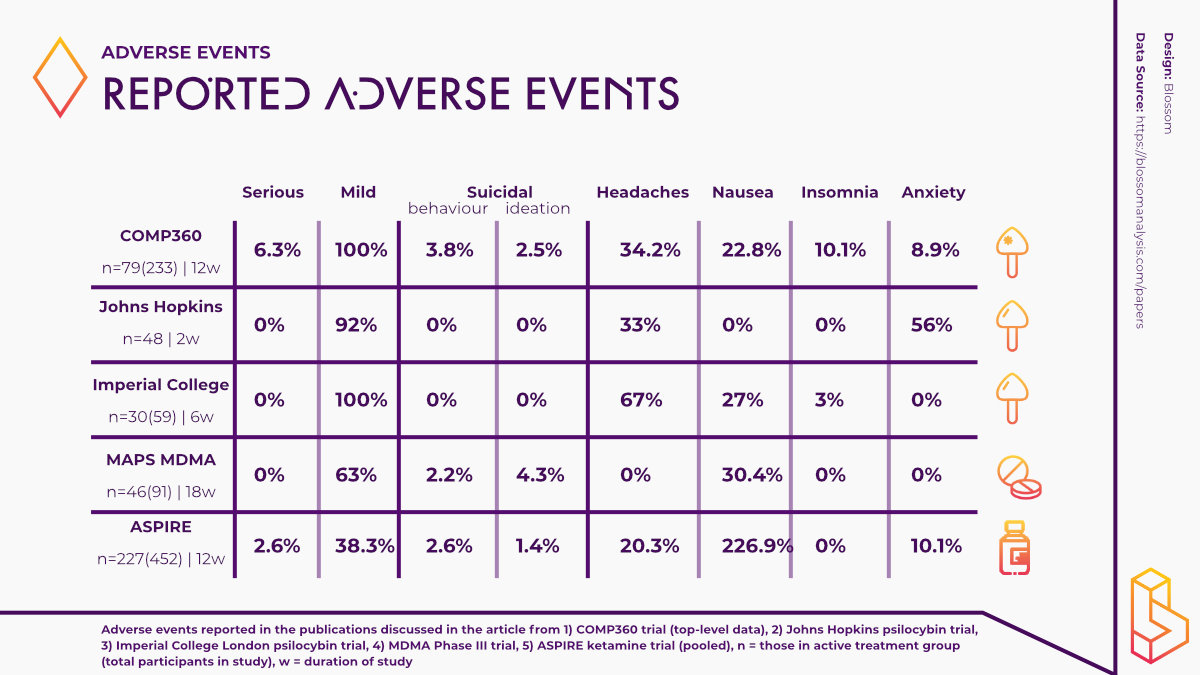

Recently, the adverse events that psychedelics are capable of inducing have come under scrutiny in wake of the results of the COMPASS Pathways COMP360 trial. In the present article, we explore the adverse events of this trial.

Furthermore, in order to contextualize the adverse events reported in the trial within the realm of psychedelic research as a whole, we look at a select number of clinical trials involving psychedelics and the adverse events they have reported.

Largest psilocybin trial to date

The COMP360 trial was a Phase IIb study exploring the effects of COMP360, their synthetic version of psilocybin, on patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD). The trial was the largest study with psilocybin to date, with 233 participants administered psilocybin in conjunction with psychological support.

Prior to the release of the official publication, COMPASS has just released the main findings from the trial in a press release. It was found that a single dose of psilocybin (25mg) administered in conjunction with psychological support led to a statistically significant drop in depression.

The treatment difference was -6.6 points change from baseline in the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total scores when compared to the control group. Moreover, the 25mg group demonstrated statistically significant efficacy from the day after the COMP360 psilocybin administration.

It should be noted that the antidepressant effects of 25mg of psilocybin in the majority of participants were not sustained. Such findings emphasize the fact that psychedelics are not a silver bullet aimed at global mental health as many people are led to believe. Like many other treatments, psychedelics won’t be for everyone.

While these results are predominantly positive, they are somewhat overshadowed by the reporting of adverse events experienced by some of the trial participants. 179 of the trial participants reported an adverse event however, more than 90 per cent of these adverse events were mild or moderate in severity.

The most commonly reported adverse events included; headache, nausea, fatigue and insomnia.

Noteworthily, a total of 12 patients reported experiencing a serious adverse event (SAE) such as suicidal behaviour, intentional self-injury, and suicidal ideation (three patients) after psilocybin administration. Such findings raise a number of questions and cannot be ignored if psychedelics are going to become a viable therapy option.

For example, it is important that we establish if it was the effects of psilocybin that led to these SAEs or if the treatment-resistant nature of the participants’ depression persisted following psilocybin-assisted therapy.

In order to gain a better perspective on adverse events in clinical trials involving psychedelics, we have gathered data on adverse events that have been reported in previously conducted clinical trials involving psychedelics.

Earlier psilocybin studies adverse events

In their 2016 study using psilocybin to treat depression, Robin-Carhart Harris and the team at Imperial College London reported no serious adverse events in the study population and adverse events they did report were mild in severity.

The most commonly reported adverse events in this study were transient anxiety, headaches and nausea. These events were also expected as a result of the psychological effects of psilocybin.

In the six-month follow-up to the aforementioned study, no adverse events were reported.

At Johns Hopkins, the research team reported similar findings in their study using psilocybin to treat major depressive disorder (MDD). No SAEs were reported and the adverse events that were reported were transient and mild severity including challenging emotional experiences and headaches.

A recent study comparing the effects of psilocybin to the antidepressant escitalopram found that the reporting of adverse events was similar across the psilocybin and escitalopram groups. While no SAEs were reported, it is worth noting that the escitalopram reported higher incidences of anxiety when compared to the psilocybin group.

Earlier MDMA studies adverse events

MAPS have been making significant progress with regards to using MDMA-assisted therapy to treat PTSD. In their Phase III study with MDMA, the research team reported that MDMA did not induce adverse events of abuse potential, suicidality or QT prolongation (an extended interval between the heart contracting and relaxing). However, two participants randomized to the control group did report suicidal ideation during the trial.

One participant in the MDMA group also chose to discontinue participating in the study after experiencing an adverse event of depressed mood following an experimental session. Researchers noted that this participant met the criterion of a non-responder. Overall, adverse events in the MDMA group were moderate in severity and included muscle tightness, decreased appetite, nausea, hyperhidrosis and feeling cold.

The Phase II trial, which preceded the aforementioned study, reported adverse events in the active groups (i.e those who received MDMA) and these events increased with higher doses of MDMA. Furthermore, some participants reported feeling anxious, depressed mood and being irritable seven days post-treatment.

The researchers postulated that these lasting psychiatric effects may be part of the psychotherapeutic process of recalling and discussing experiences, thoughts, and emotions related to traumatic events, and also possibly be a direct pharmacological effect of MDMA.

Earlier ketamine studies adverse events

Prior to esketamine being sold under the brand name Spravato, its manufacturers Janssen Pharmaceuticals were tasked with subjecting the substance to the clinical trial process. To do so, two Phase III trials were conducted; ASPIRE I and ASPIRE II.

A pooled analysis of the results of both studies found that the most commonly reported adverse events were dizziness, dissociation, nausea, somnolence, and headache. The majority of these events were resolved on the same day. Importantly, 10 patients in the esketamine group and six in the placebo group attempted suicide during the treatment phase of the studies.

However, there was insufficient evidence to infer a direct relationship between attempted suicide and esketamine. Given that the cohort in these studies were depressed individuals who had active suicidal ideation with intent, it is possible that suicide attempts were independent of esketamine. Moreover, some trial participants had a history of attempting suicide.

A randomized-controlled trial examining the safety and efficacy of administering six consecutive ketamine infusions versus five consecutive infusions of the benzodiazepine midazolam followed by a single ketamine infusion found that ketamine had a greater antidepressant effect.

Commonly reported adverse events following ketamine infusion included general malaise, decreased energy, increased blood pressure, headaches, fatigue, anxiety and nausea/vomiting.

In the midazolam plus single ketamine infusion group, similar adverse events were reported; anxiety, fatigue, nausea/vomiting, decreased energy and increased blood pressure.

The study reported two serious adverse events, one in the ketamine group and one in the midazolam group. Both patients reported experiencing headaches however, in both cases headaches were considered unrelated to the study. Ketamine was deemed to be well-tolerated in the study and no attempts at suicide were reported.

Earlier ayahuasca studies adverse events

When compared to other psychedelics, a limited number of randomized-controlled trials (RCTs) exploring the effects of ayahuasca have taken place. In spite of this, a large number of anecdotal reports from ayahuasca users exist as well as some clinical evidence.

In a recent pilot, proof-of-concept study exploring the effects of ayahuasca on the recognition of facial expressions in healthy volunteers (n=22) the following adverse events were reported; vomiting, gastrointestinal discomfort and nausea, difficulty in concentrating, headache, and drowsiness.

Vomiting, gastrointestinal discomfort and nausea are commonly reported in rituals where ayahuasca is consumed and are thought to be part of the ‘purging’ process. Furthermore, study participants did not view these effects as being negative.

A study investigating the effects of ayahuasca in people with social anxiety disorder reported similar findings. In this study, reported adverse events included gastrointestinal discomfort and nausea, vomiting, drowsiness, confusion, headache, diarrhoea, fear, distress, and dissociation/depersonalization. These effects were transient in nature and participants found them tolerable.

Implications of adverse events

The preliminary results of the COMP360 trial raise concerns regarding the safety of using psychedelics to treat mental health disorders like depression. However, from the select number of studies included in this article, psychedelics have generally been safe and well-tolerated by study participants.

In the case of adverse events being reported, they tend to be transient and mild in severity more often than not. Furthermore, serious adverse events, such as suicidal ideation, have been reported in studies where the cohort has already been experiencing such behaviours as a result of their mental health disorder.

Nonetheless, the reporting of serious adverse events in the COMP360 warrants further analysis. As the results thus far have been communicated in the form of a press release, the publishing of the official results may shed light on the matter. Whether these adverse events can be directly related to psilocybin (and/or the absence of positive effects after psilocybin) or if they were a result of the participants underlying treatment-resistant depression remains to be seen.

Given that all suicidal behaviours reported in the trial were experienced at least one month after psilocybin administration, it may be the case that psilocybin did not elicit antidepressant effects in these individuals. Moreover, perhaps the psilocybin experience led to the recalling of particularly difficult memories or experiences for the individuals in question which catalysed their suicidal behaviours.

The fact that this trial is the largest trial using psilocybin to date emphasizes the value of trials with large sample sizes. With a much higher number of participants than previously conducted trials involving psilocybin, the likelihood of adverse events occurring increased. In due time and with regulatory approval, similar studies need to take place to see if the positive findings of the COMP360 trial can be replicated.

With some significant questions left unanswered, the finalized results and the outcome of the peer review process are eagerly anticipated.

What happens next?

The select number of studies presented in this article highlight that, in general, both classic and non-classic psychedelics tend to be well tolerated in clinical trials. However, serious adverse events can still occur and can’t be ignored. Unearthing the nature of an adverse reaction to any drug is an essential part of the drug development process.

For treatment models using psychedelics to become widely accessible regulatory agencies like the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) must be sure of their safety profiles.

To do so, further large-scale trials are needed and regulatory agencies should grant their approval so that such trials can take place. COMPASS Pathways are set to begin meeting with regulatory agencies in early 2022 in order to discuss plans for a Phase III study using COMP360.

Ultimately, psychedelics are considered to be physiologically safe and have low addictive properties. Psychedelic experiences can be powerful and life-changing for people with mental health disorders as well as for healthy individuals.

Therefore, adequate care and preparation are needed for anyone planning to undergo a psychedelic journey. Psychedelics will only become the next big thing in mental health care if these substances continue to prove they’re both safe and effective throughout the clinical trial process.

References

1. Nichols, D. (2004). Hallucinogens. Pharmacology & Therapeutics.

2. Griffiths, R., Richards, W., McCann, U., & Jesse, R. (2006). Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences. Psychopharmacology.

3. Fiorella, D., Helsley, S., Rabin, R., & Winter, J. (1996). Potentiation of LSD-induced stimulus control by fluoxetine in the rat. Life Sciences. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0024320596004900?via%3Dihub

4. Johnson, M., Richards, W., & Griffiths, R. (2008). Human Hallucinogen Research: Guidelines for Safety. Journal of Psychopharmacology.

Become a psychedelic insider

Get a Pro Membership to enjoy these benefits & support Blossom📈 full reports on Topics & Compounds

🧵 full summary reviews of research papers

🚀 full access to new articles

See Memberships